Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: Geography

Context:

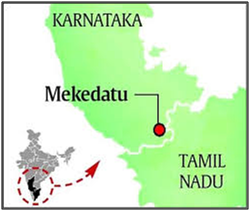

- The Supreme Court Tamil Nadu’s application challenging the proposed construction of a reservoir by Karnataka at Mekedatu across the inter-state river Cauvery as “premature”.

About Mekedatu Reservoir Project:

- Location: It is a multi-purpose (drinking water and power) project proposed by Karnataka. It is about 90 km away from Bengaluru and 4 km ahead of the border with Tamil Nadu.

- Nature: The Mekedatu project is a multipurpose project involving the construction of a balancing reservoir near Kanakapura in Ramanagara district, Karnataka.

- Nomenclature: Mekedatu, meaning goat’s leap, is a deep gorge situated at the confluence of the rivers Cauvery and its tributary Arkavathi.

- Objective: Its primary objectives are to provide drinking water to Bengaluru and neighboring areas, totaling 4.75 TMC, and generate 400 MW of power.

- Associated river: The project is proposed at the confluence of the Cauvery River with its tributary Arkavathi.

- Structure: The plan involves building a 99-metre-high, 735-metre-long concrete gravity dam, an underground powerhouse, and a water conductor system.

- Capacity of reservoir: The expected capacity of the dam is 66,000 TMC (thousand million cubic feet) of water. Once completed, it is expected to supply over 4 TMC of water to Bengaluru cityfordrinking purposes.

- Estimated cost: The estimated cost of completing the project is around Rs 14,000 crores, covering an area of over 5,000 hectares.

- Concerns: Tamil Nadu, the lower riparian state has claimed that Mekedatu area represents the last free point in Karnataka from where Cauvery water flows unrestricted into Tamil Nadu, and Mekedatu dam project is an attempt by Karnataka to lock this free flow of water.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

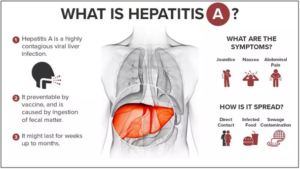

- As India debates the inclusion of the typhoid conjugate vaccine in its universal immunisation programme, it is time to ask whether Hepatitis A, a growing cause of acute liver failure deserves even greater priority.

About Hepatitis A:

- Nature: It’s a viral infection that happens after exposure to the hepatitis A virus (HAV).

- Affected organ: It is a very contagious liver disease. The infection causes inflammation in the liver.

- Risk factors: These include drinking unclean water, eating food that’s been washed or grown in unclean water, eating food that’s been handled by an infected person, close physical contact with an infected person, including having sex and sharing needles to take drugs, etc.

- Transmission: Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) usually spreads via fecal-oral route (contaminated food/water/surfaces).

- Symptoms: These include fever, fatigue, dark urine, pale stools, abdominal pain (often mild in children), etc.

- Difference with Hepatitis B and C: It is an acute, self-limiting disease. Unlike Hepatitis B and C, it does not lead to chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, or liver cancer.

- Treatment: Presently, no specific treatment exists for hepatitis A. The body clears the hepatitis A virus on its own. In most cases of hepatitis A, the liver heals within six months with no lasting damage.

- Prevention: Improved sanitation, safe water supply, proper hygiene (e.g., handwashing), and vaccination are the most effective preventive measures.

- Vaccination: A safe and effective vaccine is available. India recently launched its first indigenously developed Hepatitis A vaccine named “Havisure” (a two-dose inactivated vaccine).

- Initiatives by India: The National Viral Hepatitis Control Program (2018) in India aims to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

- Indian Railways is planning to install DRISHTI System, an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based technology to enhance the safety of freight trains.

About DRISHTI System:

- Nature: It is an AI-Based Freight Wagon Locking Monitoring System launched by Indian Railways.

- Objective: The DRISHTI system aims to tackle operational challenges in identifying unlocked or tampered doors on moving freight wagons — a persistent safety and security issue in rail logistics.

- Development: It is being developed through a collaborative initiative between the Northeast Frontier Railway (NFR) and Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Technology Innovation and Development Foundation (IITG TIDF).

- Uniqueness: The new AI-based solution is designed to provide real-time monitoring, detect anomalies in door locking mechanisms, and automatically generate alerts without disrupting train movement.

- Technologies used: It uses AI-powered cameras and sensors strategically installed to capture and analyse door positions and locking conditions. It also uses advanced computer vision and machine learning technology for the detection purposes.

- Benefits: DRISHTI is expected to improve freight security, enhance wagon sealing integrity, and reduce dependency on manual inspection processes. The traditionally manual checks are not only time-consuming but also impractical for long-haul rakes under dynamic conditions.

- Refinement: Preliminary results have shown encouraging accuracy levels, validating the potential of this indigenous innovation. Further refinements and scalability plans are underway for wider application across the NFR network to strengthen rolling stock safety and operational reliability

Source:

Category: Polity and Governance

Context:

- Union Minister for Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare participated in the ‘Plant Genome Saviour Awards Ceremony’, celebrating the Silver Jubilee of the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights (PPV&FRA) Act, 2001.

About PPV&FRA Act:

- Nature: It is a statutory body established on 11 November, 2005 under the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001.

- Nodal ministry: It works under the Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, Government of India.

- Headquarter: Its headquarters is located in New Delhi.

- Objectives:

- Grant intellectual property rights to plant breeders for their innovations in developing new plant varieties

- Recognise and reward farmers and communities who conserve traditional varieties and biodiversity

- Promote the protection of farmers’ rights to save, use, sow, resow, exchange, share, and sell farm-saved seed of registered varieties

- Encourage research and innovation in plant breeding and agriculture

- Maintain the National Register of Plant Varieties (NRPV) and ensure the documentation and conservation of valuable germplasm resources

- Structure: The Chairperson is the Chief Executive of the Authority. It has 15 members, and eight of them are ex-officio members representing various Departments/ Ministries. The Registrar General is the ex-officio Member Secretary of the Authority.

- Functions:

- Registration of new plant varieties, essentially derived varieties (EDV), extant varieties;

- Compulsory cataloging facilities for all variety of plants;

- Preservation of plant genetic resources of economic plants and their wild relatives;

- Maintenance of the National Register of Plant Varieties and National Gene Bank.

- Significance: The Authority plays a pivotal role in safeguarding farmers’ traditional knowledge and ensuring equitable benefit sharing arising from the use of indigenous varieties.

- Balance between innovation and tradition: By bridging scientific innovation and traditional wisdom, the PPV&FRA has emerged as a key instrument in protecting India’s agricultural biodiversity, ensuring seed sovereignty, and promoting sustainable development.

Source:

Category: Government Schemes

Context:

- The Union Cabinet has approved the Export Promotion Mission (EPM), a flagship initiative announced in the Union Budget 2025–26 to strengthen India’s export competitiveness, particularly for MSMEs.

About Export Promotion Mission (EPM):

- Built on collaboration: EPM is anchored in a collaborative framework involving the Department of Commerce, Ministry of MSME, Ministry of Finance, and other key stakeholders including state governments.

- Objective: It is a flagship initiative to strengthen India’s export competitiveness, particularly for MSMEs, first-time exporters, and labour-intensive sectors. It will provide a comprehensive and digitally driven framework for export promotion.

- Implementing agency: The Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) will act as the implementing agency, with all processes — from application to disbursal — being managed through a dedicated digital platform integrated with existing trade systems.

- Time Period: It has a budget outlay of Rs. 25,060 crore for FY 2025–26 to FY 2030–31.

- Strategic shift: It marks a strategic shift from multiple fragmented schemes to a single, outcome-based, and adaptive mechanism.

- Consolidation of related schemes: It consolidates key export support schemes such as the Interest Equalisation Scheme (IES) and Market Access Initiative (MAI), aligning them with contemporary trade needs.

- Priority sectors: Under EPM, priority support will be extended to sectors impacted by recent global tariff escalations, such as textiles, leather, gems & jewellery, engineering goods, and marine products.

- Sub-schemes:

- NIRYAT PROTSAHAN: It focuses on improving access to affordable trade finance for MSMEs through a range of instruments such as interest subvention, export factoring, collateral guarantees etc.

- NIRYAT DISHA: It focuses on non-financial enablers that enhance market readiness and competitiveness such as export quality and compliance support, assistance for international branding, packaging,export warehousing and logistics etc.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(UPSC GS Paper II – “Effect of policies and politics of developed and developing countries on India’s interests, Indian diaspora”)

Context (Introduction)

The global nuclear order, shaped over eight decades through treaties, norms and arms-control arrangements, is facing renewed strain as U.S. President Donald Trump’s testing signals threaten to undo the fragile mechanisms restraining nuclear competition.

Evolution of the Global Nuclear Order

- The order began after Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1945), leading to a near-universal taboo on nuclear use that has held for 80 years.

- By late 1970s, arsenals peaked at ~65,000 warheads, prompting arms-control efforts like the SALT, ABM, and later START treaties to prevent uncontrolled competition.

- The NPT (1970) institutionalised the division between five recognised nuclear-weapon states and non-nuclear states, preventing the feared spread to “two dozen” nuclear powers.

- The CTBT (1996) emerged as the next pillar, aiming to delegitimise nuclear explosive testing, though never entering into force due to missing ratifications by key Annex-II states.

- Post-Cold War mechanisms like New START (2010) brought strategic arsenals down to 1,550 deployed warheads each for the U.S. and Russia, maintaining predictability and transparency.

Current Issue: Breakdown of Restraint

- Trump’s October 2025 remarks signalling a resumption of U.S. nuclear testing—despite later clarifications of “systems-tests”—have undermined confidence in long-held norms.

- Major powers are developing new warhead types, hypersonics, and dual-use delivery systems, but have so far avoided explosive testing; Russia’s last was in 1990, U.S. in 1992.

- The CTBT norm is weakening: Russia withdrew ratification (2023); U.S., China, Israel, Iran, Egypt still not ratified; India and Pakistan remain outside, North Korea has tested six times.

- New START expires in 2026 with no dialogue underway, removing the final legally binding U.S.–Russia arms-control guardrail.

- China’s arsenal, long under 300 warheads, is expanding rapidly (estimated 600 today, expected 1,000 by 2030), complicating trilateral nuclear stability.

- Resumption of explosive tests by any major power would trigger reciprocal testing—benefiting China’s limited test data, pushing India and Pakistan to follow, and encouraging new aspirants.

Criticisms and Risks

- Erosion of CTBT norms may lead to qualitative arms racing, modernisation and miniaturisation of low-yield “more usable” weapons.

- Dual-use hypersonics and autonomous systems heighten ambiguity, increasing risk of miscalculation.

- Collapse of the remaining U.S.–Russia architecture removes verification and transparency mechanisms essential for crisis stability.

- Nuclear taboo—central to global security for eight decades—faces dilution amid strategic distrust and high-tech arms developments.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Build a new nuclear order reflecting multipolar geopolitics—bringing China formally into arms-control frameworks.

- Revive CTBT momentum through political commitments, expanded monitoring authority, and strengthened verification.

- Reinforce no-first-use or “sole purpose” doctrines to preserve strategic stability.

- Enhance transparency in hypersonics, space and cyber capabilities through confidence-building agreements.

- For India: sustain voluntary moratorium, monitor regional responses, and fortify diplomacy for universal non-proliferation norms.

Conclusion

The nuclear order crafted in the 20th century is no longer adequate for today’s fractured geopolitics. As major powers revisit testing and modernise arsenals, safeguarding the nuclear taboo and reimagining arms control become essential to prevent an uncontrolled, multi-actor nuclear race.

Mains Question

- “Trace the evolution of the global nuclear order since 1945. How do recent signals of resuming nuclear tests threaten the stability of the present non-proliferation regime?” (250 words, 15 marks)

(UPSC GS Paper II – “Issues relating to development and management of health, healthcare and related services”)

Context (Introduction)

The WHO’s GLASS 2025 report highlights AMR in India as one of the world’s most severe threats, with one in three infections resistant to common antibiotics. This escalating challenge requires urgent surveillance, stewardship, public awareness, and sustained investment.

Main Arguments

- GLASS 2025 confirms India’s AMR burden is among the highest worldwide, driven by high infectious disease load, misuse of antibiotics, and weak regulatory enforcement.

- One in three bacterial infections in India (2023) is resistant to commonly used antibiotics, far above the global figure of one in six.

- Resistance is particularly high in E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, especially in ICUs where antibiotic pressure is intense.

- Surveillance gaps persist: Most Indian data come from tertiary-care hospitals, ignoring community and rural infections, thereby producing non-representative, skewed estimates.

- India has surveillance mechanisms (ICMR’s AMRSN/i-AMRSS and NCDC’s NARS-Net) but lacks geographical density and uniform participation.

- Implementation of India’s National Action Plan on AMR (NAP-AMR) has been slow; only Kerala has shown significant results through One Health collaboration, OTC-ban enforcement (AMRITH), and AMR literacy campaigns.

Criticisms / Drawbacks Highlighted

- Surveillance limitations: Tertiary hospitals overrepresent severe infections, exaggerating national averages and masking community-level patterns.

- Regulatory failures: OTC antibiotic sales, incomplete treatment courses, and environmental contamination from pharma and hospital waste remain poorly controlled.

- Slow State-level action: Except Kerala, most States have not operationalised AMR plans; coordination across human, animal, and environmental sectors is limited.

- Public disconnect: AMR feels abstract to citizens; lack of awareness fuels misuse.

- Thin antibiotic pipeline: Only a handful of truly innovative antibiotics exist globally; India has approved a few new agents but LMIC access gaps remain.

- Funding shortages: Minimal investment in surveillance expansion, innovation, diagnostics, and stewardship programmes undermines long-term response capacity.

Reforms and Strategies (from article + India’s broader research)

- Strengthen Nationwide Surveillance

- Expand beyond medical colleges by integrating 500+ NABL labs and building microbiology capacity in district and primary-level facilities.

- Adopt a full-network model for real-time, representative AMR estimates.

- Enhance Antibiotic Stewardship

- Enforce prescription-only sales; scale Kerala’s AMRITH model nationally.

- Implement strict monitoring of hospital antibiotic practices, especially in ICUs.

- Regulate antibiotic discharge from pharma units and hospitals to minimise environmental spread.

- Promote One Health Coordination

- Ensure coordination across human medicine, veterinary sectors, aquaculture, and environment—currently fragmented despite NAP-AMR goals.

- Replicate Kerala’s inter-sectoral model through State Action Plans.

- Improve Public Awareness & AMR Literacy

- Launch national campaigns that humanise AMR impacts, involving large nonprofits, patient advocates, community health workers, and schools.

- Aim for “antibiotic-literate” communities through localised campaigns.

- Boost Innovation, R&D, and Industry Partnership

- Support new antibiotic development with incentives for novel mechanisms of action targeting WHO’s priority MDR pathogens.

- Promote participation in global networks like the AMR Industry Alliance to improve diagnostics, innovation access, and responsible manufacturing.

- Sustained Funding & Policy Commitment

- Increase long-term investment in surveillance systems, antibiotic research, public health labs, and stewardship programmes.

- Develop a national AMR financing window with State–Centre cost-sharing.

Conclusion

India’s AMR crisis represents a slow-burning public health emergency. While Kerala shows that coordinated action, public awareness, and strict enforcement can reverse resistance trends, the national response remains fragmented. To “secure the future,” India must expand surveillance, regulate antibiotic misuse, foster innovation, and build societal understanding—transforming AMR from an abstract technical concept into a national health priority.

Mains Question

- “India’s antimicrobial resistance crisis reflects weaknesses in surveillance, stewardship, and public awareness. In the light of the GLASS 2025 report, evaluate the reforms needed to build a robust AMR response.” (250 words, 15 marks )