Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: Polity and Governance

Context:

- Supreme Court said that CJI must deal with claim that HC judge approached National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) member on order.

About National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT):

- Nature: The NCLAT is a quasi-judicial body constituted under Section 410 of the Companies Act, 2013. It was established to hear appeals against the decisions of the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), functioning since 1st June 2016.

- Objective: Its main objective is to promote timely corporate dispute resolution, ensure transparency, and improve efficiency in insolvency and corporate governance matters.

- Functions:

- Hearing appeals against orders of NCLT under Section 61 of IBC.

- Hearing appeals against orders of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI) under Sections 202 and 211 of IBC.

- Hearing appeals against orders of the Competition Commission of India (CCI).

- Hearing appeals related to the National Financial Reporting Authority (NFRA).

- Giving advisory opinions when legal issues are referred by the President of India.

- Headquarters: Its headquarters is located in New Delhi.

- Composition: It includes a Chairperson, along with Judicial and Technical Members, all appointed by the Central Government based on expertise in law, finance, accountancy, and administration.

- Regulation: It can regulate its own procedure and possesses powers equivalent to a civil court under the Civil Procedure Code, 1908.

- Powers: It can summon witnesses, receive affidavits, enforce production of documents, and issue commissions. Orders passed by NCLAT are enforceable like civil court decrees.

- Appeals: Appeals against NCLAT orders can be filed in the Supreme Court of India.

- Exceptions: Civil courts have no jurisdiction over matters within the purview of NCLAT. No court or authority can grant injunctions against any action taken by NCLAT under its legal authority.

- Disposal of appeals: NCLAT is required to dispose of appeals within six months from the date of receipt to ensure swift resolution.

Source:

Category: Miscellaneous

Context:

- Marble from Ambaji, Gujarat’s prominent pilgrimage site and Shaktipeeth, has been awarded the Geographical Indication (GI) tag for its high-quality white stone.

About Ambaji Marble:

- Nature: It is a type of marble known for its stunning white appearance and unique natural patterns.

- Nomenclature: It is named after the town of Ambaji in the state of Gujarat, where it is predominantly quarried. It is also known as Amba White Marble and Ambe White Marble.

- Uniqueness: It is characterized by its pristine white colour, which often features subtle grey or beige veining. It has very long-lasting shine and durability.

- Distinctive variations: The veins can vary in intensity, ranging from fine and delicate to bold and pronounced, giving each slab a distinct and individualistic appearance. These variations occur naturally due to the presence of minerals and impurities during the marble formation process.

- Uses: The smooth and polished surface of the marble adds to its appeal and sophistication. It is widely used for luxury architectural projects, sculptures, and monuments.

About Geographical Indication (GI) Tag:

- Nature: A GI tag is a name or sign used on certain products that correspond to a specific geographical location or origin.

- Objective: The GI tag ensures that only authorised users or those residing in the geographical territory are allowed to use the popular product name. It also protects the product from being copied or imitated by others.

- Validity: A registered GI is valid for 10 years and can be renewed.

- Nodal ministry: GI registration is overseen by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

- Legal framework: It is governed by Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

- According to a new study, Vitamin D deficiency may quietly raise the risk of heart diseases.

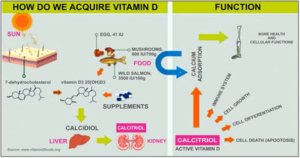

About Vitamin D:

- Nature: Vitamin D (also referred to as calciferol) is a fat-soluble vitamin.

- Production: It is produced endogenously when ultraviolet (UV) rays from sunlight strike the skin and trigger vitamin D synthesis. During periods of sunlight, vitamin D is stored in fat and then released when sunlight is not available.

- Foods rich in vitamin D: Very few foods have vitamin D naturally. The foods with the most are fatty fish (like salmon and tuna), liver, mushrooms, eggs, and fish oils. Further, food companies often “fortify” milk, yogurt, baby formula, juice, cereal, and other foods with added vitamin D.

- Importance: Vitamin D promotes calcium absorption and helps maintain adequate levels of calcium and phosphorus in the blood, which is necessary for healthy bones and teeth. Without sufficient vitamin D, bones can become thin, brittle, or misshapen.

- Role in cell growth: Vitamin D has other roles in the body, including reduction of inflammation as well as modulation of such processes as cell growth, neuromuscular and immune function, and glucose metabolism.

- Deficiency: A lack of vitamin D can lead to bone diseases such as osteoporosis or rickets. Osteoporosis is a disease in which your bones become weak and are likely to fracture (break). Chronic and/or severe vitamin D deficiency, can also lead to hypocalcemia (low calcium levels in your blood).

- Persons prone to its deficiency: Anyone can have vitamin D deficiency, including infants, children and adults. Its deficiency may be more common in people with higher skin melanin content (darker skin) and who wear clothing with extensive skin coverage, particularly in Middle Eastern countries.

Source:

Category: Environment and Ecology

Context:

- Global Cooling Watch 2025, launched recently at COP30 in Belém, Brazil, finds that cooling demand could more than triple by 2050 under business as usual.

About Global Cooling Watch Report:

- Nature: The Global Cooling Watch 2025 is UNEP’s second global assessment on the environmental, economic, and equity dimensions of cooling, providing the scientific foundation for the Global Cooling Pledge.

- Publishing agency: It is published by United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

- Objective: It aims to analyse global cooling trends, project future emissions, and propose a “Sustainable Cooling Pathway” to achieve near-zero emissions while ensuring equitable access to cooling worldwide.

- Key highlights of Global Cooling Watch Report 2025:

- Global cooling capacity is projected to rise 2.6 times by 2050, driven by rapid urbanization, income growth, and intensifying heatwaves, particularly in developing nations.

- Cooling demand in Article 5 countries (developing nations) is set to increase fourfold, highlighting a widening divide in energy use and infrastructure readiness between rich and poor economies.

- Global electricity use for cooling may rise from 5,000 TWh (2022) to 18,000 TWh (2050), straining power grids and escalating peak load demands, especially in tropical regions.

- Phasing down high-global-warming refrigerants (HFCs) and adopting low-GWP alternatives could eliminate up to 0.4°C of projected global warming this century.

- So far, 72 nations and 80 organizations have joined the Global Cooling Pledge, collectively aiming for a 68% emission reduction in the cooling sector by 2050.

Source:

Category: Defence and Security

Context:

- Chief of the Air Staff recently inaugurated the Mudh-Nyoma airbase in Ladakh by landing a C-130J special operations aircraft there.

About Mudh-Nyoma Airbase:

- Location: It is an Indian Air Force (IAF) base located in Nyoma, in southeastern Ladakh. It lies close to the southern bank of the Pangong Tso and earlier had a mud-paved landing ground.

- Near LAC: It is located at a height of 13,700 feet and is 23 km from the contested Line of Actual Control (LAC) with China.

- History: It was originally built as a mud-paved landing ground in 1962, but it remained inactive for decades. It was reactivated in 2009 when an AN-32 aircraft landed successfully. Further, following the 2020 India–China border standoff, Nyoma ALG supported operations of C-130J, AN-32, Apache, and Chinook aircraft.

- Uniqueness: Nyoma is the fourth IAF base in Ladakh, the highest airfield in the country, and the fifth highest in the world now.

- Organisation responsible for upgradation: The responsibility of upgrading the airbase was entrusted to the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) under Project Himank. The upgrade included extending the original airstrip into a 2.7 km ‘rigid pavement’ runway, a new ATC complex, hangars, a crash bay, and accommodation.

- Features: The airfield is designed to house a number of military unmanned, rotary-wing, fixed-wing aircraft, including heavier transport planes, like the C-17 Globemaster III, and fighter jets, like the Sukhoi-30MKI.

- Designed to operate below minus 20°C: The infrastructure at the airbase includes necessary facilities for maintenance and sustaining air and ground crews, essential for operations in a region where winter temperatures can plummet to below minus 20°C.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(UPSC GS Paper III – “Conservation, environmental pollution, degradation and climate change”)

Context (Introduction)

The Global Carbon Project’s 2025 report warns that global emissions will hit a record high, keeping the world on a 2.6°C trajectory. COP-30 negotiators in Brazil face urgent pressure to accelerate clean energy and strengthen people’s climate resilience.

Main Arguments

- Global emissions nearing historic peak: Emissions are projected to reach a record high in 2025. The US shows the highest increase (1.9%), followed by India (1.4%) and China/EU (0.4%). Rising demand offsets clean-energy progress.

- India’s carbon intensity declining: Slower emission growth stems from large renewable deployment, a cooler summer, and early monsoon, causing a fall in electricity-sector emissions. Long-term carbon intensity is improving — GHG growth dropped from 6.4% (2004–15)to 3.6% (2015–24).

- Renewables exceed coal but pace inadequate: Renewables have overtaken coal as the largest electricity source worldwide. Yet fossil-fuel dependence persists because energy consumption continues to grow, especially in fast-developing countries.

- Paris temperature target slipping away: At current rates, the world is on track for 2.6°C warming, far above the 1.5°C goal. Carbon budgets for 1.5°C may be exhausted within the decade, leaving little leeway for error or delay.

- COP-30 must deliver a clean-energy roadmap: The COP-30 must provide concrete directions for expanding renewables and building climate-resilient infrastructure to protect lives and livelihoods from floods, droughts, and cyclones.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- Slow decarbonisation despite renewable progress: Global mitigation efforts are insufficient. Fossil-fuel use remains embedded in transport, industry, and thermal power.

- Reversal in developed economies: The surge in US emissions breaks a nearly 20-year downward trajectory, weakening global leadership credibility and burden-sharing expectations.

- Weak adaptation investment: Financing for climate resilience — flood defences, drought management, cyclone preparedness — remains far below required levels. Vulnerable communities continue to face high climate risks.

- Energy-security constraints in developing economies: Countries like India cannot abruptly abandon fossil fuels without jeopardising growth and energy access. This complicates uniform global expectations.

- Gaps in global collective action: Post-Paris cooperation has stagnated. Vague commitments such as “phase-down of unabated coal” leave room for interpretation and delay.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Scale Clean Energy Deployment: Expand solar, wind, and green hydrogen manufacturing; modernise grids; enhance battery storage capacity. India’s renewable capacity (200+ GW) should be complemented with round-the-clock storage solutions.

- Strengthen Climate Resilience Investments: Prioritise climate-resilient housing, urban drainage, cyclone shelters, drought-proof agriculture, and heat-action plans. UN estimates show adaptation financing needs to grow five- to ten-fold for developing nations.

- Establish Time-bound Fossil-Fuel Transition Pathways: COP-30 should adopt firm timelines on fossil-fuel phase-down and expand climate finance beyond the long-pending $100-billion commitment. Developed nations must undertake deeper absolute cuts.

- Build Just and Equitable Energy Transitions: Ensure technology transfer, concessional climate finance, and affordable capital for the Global South. Energy poverty concerns must be balanced with global climate goals.

- People-Centric Climate Security: Increase early-warning systems, livelihood protection schemes, and community-based adaptation. Investments should prioritise vulnerable groups exposed to floods, droughts, sea-level rise, and heat waves.

Conclusion

The Global Carbon Project’s findings underline a critical truth: clean-energy expansion alone cannot stabilise the climate unless accompanied by deep decarbonisation and strong resilience-building. COP-30 offers an opportunity to reconcile both — delivering a roadmap that accelerates clean energy and safeguards vulnerable populations from intensifying climate impacts.

Mains Question

- “The Global Carbon Project highlights rising global emissions despite rapid renewable expansion. In this context, examine the need for clean-energy investment and climate resilience as twin pillars of future climate policy.” (250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Indian Express

(UPSC GS Paper III – “Indian Economy: Monetary policy, Inflation and Growth”)

Context (Introduction)

India’s Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) framework—mandating a 4% inflation target with a ±2% band—comes up for review in March 2026. The RBI’s discussion paper reopens key questions on headline vs. core inflation, acceptable inflation levels, and the applicable target band.

Main Arguments

- FIT has stabilised inflation despite shocks: Since adoption in 2016, inflation has remained broadly range-bound, even through episodes such as COVID-19, commodity spikes, and supply disruptions. The framework improved policy predictability and institutional autonomy.

- Headline inflation is the appropriate target: Because inflation affects savings, investments, and disproportionately harms the poor, the headline inflation, not core inflation, should be targeted. Food inflation often reflects monetary conditions, not merely supply shocks.

- Monetary policy influences general price level: As Friedman had said that without expansion in overall liquidity, sustained inflation cannot occur. Food inflation can create second-round effects—through wages and cost pass-through—making it relevant for monetary policy.

- Acceptable inflation for India is around 4%: Historical data (since 1991, excluding the COVID year) show a non-linear inflation–growth relationship, with a turning point near 3.98%. This supports continuing the 4% target. Simulations for 2026–2031 also suggest inflation below 4% as consistent with stable growth.

- The current ±2% band provides adequate flexibility: The existing 2–6% tolerance band has helped the RBI manage shocks. However, the article warns that staying persistently near the upper bound undermines the spirit of FIT, especially since growth declines sharply beyond 6%.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- Debate confused between relative and general prices: Public discourse often overlooks that food-price movements reflect both supply shocks and monetary expansion. Without distinguishing these, arguments for core inflation targeting become misleading.

- Phillips Curve evidence weak in India: India’s data show only a short-run inflation–growth trade-off; long-run trade-offs are unconvincing. High inflation eventually harms growth, reinforcing the case for a firm target.

- Risk of fiscal slippage undermining FIT: Historically, monetisation of fiscal deficits in the 1970s–80s caused chronic inflation. FIT works only when complemented by fiscal discipline under FRBM. Weakening either framework harms macro stability.

- Lack of clarity on duration near upper band: The current framework does not specify how long inflation can remain near 6% without triggering accountability mechanisms, diluting the credibility of the target.

- Arguments for higher targets lack empirical basis: Preliminary empirical simulations indicate no justification for raising the target above 4%. Higher targets risk unanchoring expectations and reducing the RBI’s credibility.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Retain headline CPI as the primary target: Given India’s consumption patterns and the welfare impact of food inflation, headline CPI remains the most relevant indicator for policy credibility and public welfare.

- Maintain the 4% target with stricter accountability norms: A mid-course review mechanism could be introduced to scrutinise policy stance if inflation remains close to 6% for prolonged periods.

- Strengthen FRBM–FIT coordination: Fiscal dominance must be avoided. Clear fiscal glide paths, reduced off-budget borrowings, and better debt transparency will support monetary policy effectiveness.

- Improve inflation forecasting and food-market reforms: Strengthen early-warning systems for food inflation; improve agri-logistics, cold chains, and storage to reduce supply volatility. Better forecasting reduces policy lags.

- Conduct periodic empirical assessments of threshold inflation: Every review cycle (5 years) should incorporate updated structural models to determine threshold inflation levels consistent with evolving growth prospects, external risks, and fiscal realities.

Conclusion

India’s experience since 2016 shows that FIT has anchored expectations and contained inflation despite repeated shocks. Evidence suggests that a 4% target with a ±2% band strikes a practical balance between stability and flexibility. Going forward, policy success will depend on maintaining fiscal discipline, refining inflation forecasting, and ensuring that headline inflation—not just core—remains firmly under control.

Mains Question

- “India’s Flexible Inflation Targeting framework is due for review in 2026. Critically examine whether the 4% target with a ±2% band remains appropriate in light of India’s inflation–growth dynamics.” (250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Hindu