Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: 6th Schedule

Context:

- The Leh Apex Body (LAB), which is spearheading an agitation over Statehood and Sixth Schedule status for Ladakh, submitted a draft proposal to the Ministry of Home Affairs.

About 6th Schedule:

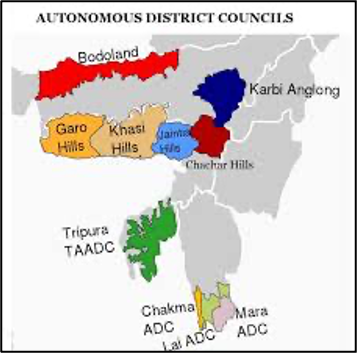

- Constitutional provision: The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, under Article 244(2) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution, is provided for the administration of tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

- Objectives:

- To protect tribal land and resources and prohibits the transfer of such resources to non-tribal individuals or communities.

- To ensure the tribal communities are not exploited or marginalized by non-tribal populations and that their cultural and social identities are preserved and promoted.

- Creation of Autonomous districts and autonomous regions:

- The tribal areas in the four states of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram are to be administered as Autonomous Districts.

- If there are different Scheduled Tribes in an autonomous district, the Governor can divide the district inhabited by them into Autonomous Regions.

- The Governor is empowered to organize and reorganize the autonomous districts. He can also increase, decrease the boundaries or alter the name of any autonomous district.

- Constitution of District Councils and Regional Councils:

- There shall be a District Council for each autonomous district consisting of not more than 30 members, of whom not more than four persons shall be nominated by the Governor, and the rest shall be elected on the basis of adult suffrage.

- There shall be a separate Regional Council for each area constituted an autonomous region.

- Powers of the District Councils and Regional Councils:

- The District and Regional councils are empowered to make laws on certain specified matters like lands, management of forest (other than the Reserved Forest), inheritance of property, etc.

- These councils also empowered to make law for the regulations and control of money-lending or trading by any person other than Scheduled Tribe residents in that Scheduled District.

- However, all laws made under this provision require the assent of the Governor of the State.

- Administration of justice in autonomous districts and autonomous regions:

- The District and Regional Councils are empowered to constitute Village and District Council Courts for the trial of suits and cases where all parties to the dispute belong to Scheduled Tribes within the district.

- The High Courts have jurisdiction over the suits and cases which is specified by the Governor.

- However, the Council Courts are not given the power to decide cases involving offenses punishable by death or imprisonment for five or more years.

- Exceptions: To autonomous districts and autonomous regions, the acts of Parliament or the state legislature do not apply or apply with specified modifications and exceptions. The Governor can appoint a commission to investigate and provide a report on any issue pertaining to the autonomous districts or regions.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

- India is a key part of global transition to a self-reliant hydrogen economy, Dr. Jitendra Singh said while addressing 3rd International Conference on Green Hydrogen.

About Green Hydrogen:

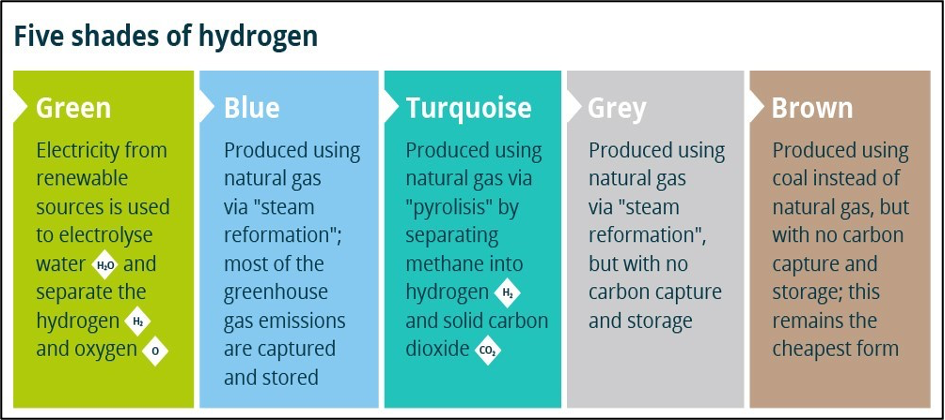

- Definition: Green Hydrogen refers to hydrogen produced through electrolysis, where renewable energy sources like solar, wind, or hydro are used to split water molecules (H₂O) into hydrogen (H₂) and oxygen (O₂). It can also be produced via biomass gasification, a process that converts biomass into hydrogen-rich gas.

- Applications: Its uses include a wide range of applications such as Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs), aviation and maritime transport, and various industrial sectors like fertilizers, refineries, and steel. It also holds potential in road and rail transport, shipping, and power generation.

- Various methods of producing Green Hydrogen:

- Alkaline electrolysis: The most mature technology, uses an alkaline solution (KOH or NaOH) as the electrolyte. Despite its high efficiency and low cost, it requires expensive materials like nickel and platinum as electrodes.

- Proton exchange membrane electrolysis: An advanced method using a solid polymer membrane as the electrolyte. It offers higher efficiency and faster response times, but the high cost of the membrane and precious metal catalysts is a challenge.

- Solid oxide electrolysis: A high-temperature process (700°C to 1000°C) using a solid ceramic material as the electrolyte. It offers high efficiency and the potential for co-electrolysis (simultaneous conversion of water and CO2 into H2 and CO), but the high temperatures and need for specialised materials make it more complex and expensive.

- Initiatives taken by India towards production of Green Production:

- Financial funding: India has sanctioned a $2 billion incentive scheme to boost green hydrogen production. The initiative aims to improve the affordability of green hydrogen, positioning India as a significant exporter. Presently, the cost of green hydrogen in India is $4-5 per kg.

- National Green Hydrogen Mission: Initiated in January 2023, this mission targets an annual production of 5 million metric tonnes of green hydrogen by 2030, leveraging 125 gigawatts of renewable energy.

- SIGHT program: It is a part of National Green Hydrogen Mission and offers substantial financial backing to boost domestic electrolyser manufacturing and green hydrogen production, reinforcing India’s vision to emerge as a leading green hydrogen economy.

Source:

Category: Government Schemes

Context:

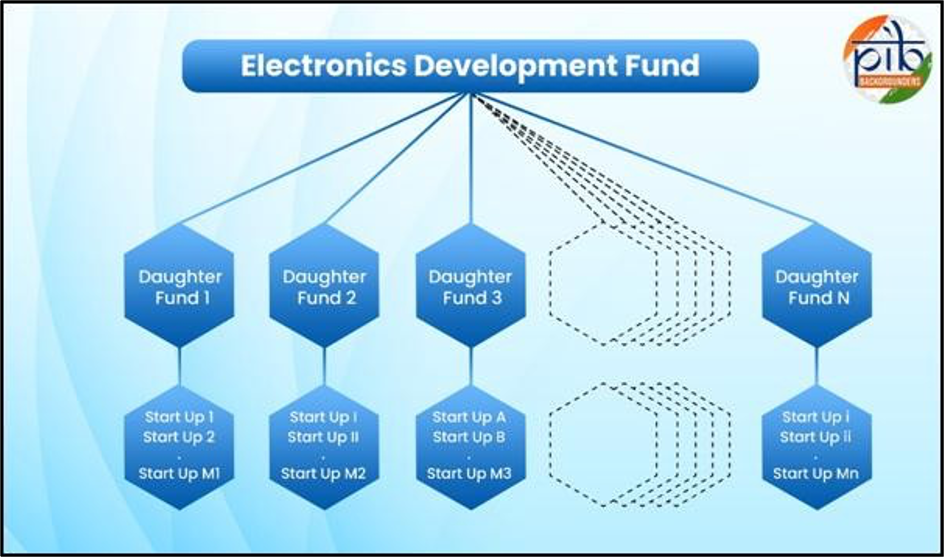

- With ₹257.77 crore invested, the Electronics Development Fund has supported 128 startups nationwide.

About Electronics Development Fund (EDF):

- Launch: The Government of India had launched the Electronics Development Fund (EDF) on 15 February 2016.

- Objective: The Fund aims to promote research, development, and entrepreneurship in the fields of electronics, nano-electronics, and information technology.

- Acts as a fund of funds: The EDF functions as a Fund of Funds, designed to invest in professionally managed Daughter Funds such as early-stage angel and venture funds. These Daughter Funds, in turn, provided risk capital to startups and companies developing new technologies.

- Key objectives of EDF include:

- To foster research and development in electronics, nano-electronics, and information technology by supporting market-driven and industry-led innovation.

- To invest in professionally managed Daughter Funds such as early-stage angel and venture funds that, in turn, provide capital to startups and technology ventures.

- To nurture entrepreneurship by supporting companies involved in the creation of new products, processes, and technologies within the country.

- To enhance India’s capacity for indigenous design and development in the Electronics System Design and Manufacturing (ESDM) sector.

- To generate a strong base of intellectual property in key technology areas and encourage ownership of innovation within India.

- To enable acquisition of foreign technologies and companies where such products are imported in large volumes, promoting self-reliance and reducing import dependence.

- Main Features of EDF:

- EDF participates in Daughter Funds on a non-exclusive basis, allowing wider collaboration and participation across the industry.

- The share of EDF in a Daughter Fund’s total corpus is determined by market requirements and the capacity of the Investment Manager to administer the fund in accordance with EDF’s policy guidelines.

- EDF generally maintains a minority participation in each Daughter Fund, encouraging greater private investment and professional fund management.

- Investment Managers of Daughter Funds are given flexibility and autonomy to raise corpus, make investments, and monitor portfolio performance.

- EDF participation is available across the entire value chain of electronics, information technology, and related ecosystems, ensuring comprehensive sectoral coverage.

- The final selection of Daughter Funds is carried out after detailed due diligence by the Investment Manager.

- Achievements:

- The Electronics Development Fund (EDF) has made remarkable progress in nurturing India’s innovation ecosystem. EDF has drawn a total of ₹216.33 crore from its contributors, including ₹210.33 crore from MeitY.

- The supported startups operate in frontier areas such as Internet of Things (IoT), Robotics, Drones, Autonomous Vehicles, HealthTech, Cyber Security, and Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, positioning India as a hub for advanced technological innovation.

Source:

Topic: Defence and Security

Context:

- The Indian Air Force (IAF) is participating in the 8th edition of the bilateral air Exercise ‘Garuda 25’ with the French Air and Space Force (FASF) at Mont-de-Marsan, France.

About Exercise Garuda 2025:

- Origin: First held in 2003, Garuda is one of India’s longest-running air exercises with a Western nation. It reflects deepening defence and strategic ties under the India–France Strategic Partnership (established in 1998).

- Objective: It is held alternately in India and France to promote operational interaction, mutual learning, and enhanced interoperability between the two Air Forces.

- Deployment of fighter jets: The IAF has deployed six Su-30MKI fighter jets, supported by IL-78 refuellers and C-17 Globemasters, to operate alongside French Rafale and other multirole fighters in complex simulated air combat missions.

- Focus Areas: It focuses on air-to-air combat drills, air defence missions, joint strike operations, and the refinement of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs).

- Importance: This exercise promotes India-France collaborations like Rafale deal, Indo-Pacific cooperation, and joint space defence research.

- Other Exercises with France: It includes Exercise Varuna (naval), and Exercise Shakti (army) and Exercise Desert Knight (India, France, and UAE).

Source:

Category: Polity and Governance

Context:

- In a first-of-its-kind move, the Army is planning to induct women soldiers in its Territorial Army (TA) battalions.

About Territorial Army:

- Establishment: It was established by Territorial Army Act, 1948; and was formally launched on October 9, 1949.

- Composition: It comprises of a volunteer reserve force comprising part-time “citizen soldiers” from civilian backgrounds (businessmen, professionals).

- Objective: It aims to relieve the regular Army from non-combat duties and augment its manpower during conflict or crisis.

- Nodal ministry: It comes under Ministry of Defence, Government of India.

- Governed by: It is governed by Territorial Army Act, 1948 and Rule 33 of the Act permits full mobilisation during national exigencies.

- Objectives: It supports army operations during war, terrorism, or border tension. It assists civil administration during floods, earthquakes, and pandemics. It also aids in counter-insurgency and stability operations in conflict-prone areas.

- Evolution: It evolved from the Indian Territorial Force (1920), which saw action in global conflicts like WWI and the Boer War. After the independence, it was established to serve as the second line of defence and engage citizens in nation-building through defence service.

- Eligibility: Indian citizens aged 18–42, who are medically fit (with civilian occupations) are eligible to join Territorial Army.

- Training Model: It consists of approximately 2 months of annual training (no full-time military obligation in peace times).

- Operational Participation: It provided logistical support, rear area defence, and vital infrastructure protection during 1947–48, 1962, 1965, 1971 wars. It also guarded ammunition dumps, supply lines, and sensitive zones during Kargil Conflict (1999).

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(UPSC GS Paper II – “Structure, organisation and functioning of the Judiciary”)

Context (Introduction)

India’s subordinate courts face severe pendency (4.69 crore cases as per NJDG), procedural delays, inexperienced judicial recruits, and outdated laws. The Supreme Court recently linked stagnation in the lower judiciary with systemic inefficiencies and rising litigation.

Main Arguments

- Clerical burden on subordinate judiciary: Subordinate judges spend mornings issuing summons, calling cases, receiving vakalatnamas, and noting appearances, leaving little time for hearings and judgments. Listing work continues past noon, reducing quality judicial time.

- Need for a specialised “ministerial court”: A lower-tier judicial officer in each district could handle ministerial tasks throughout the day—summons, ex parte evidence, filing, pleadings—freeing regular courts for trials and arguments from 10:30 a.m. onward.

- Declining quality and experience of judicial entrants: Earlier, district munsifs came with 10+ years of practice under senior lawyers. Now, fresh graduates with no exposure face difficulties in workload, reasoning, and drafting orders. Some reportedly struggle to pass basic orders.

- Inadequate training: High Court–attached training for months—observing judicial conduct, interaction with bar, drafting orders—is suggested as a way to build practical knowledge and work culture.

- Procedural laws inadvertently creating delays: New statutory mechanisms, intended for faster disposal, often slow down litigation:

-

- Commercial Courts Act Section 12(A)— mandatory pre-suit mediation often unnecessary where parties have exchanged notices.

- Marriage Laws— mandatory six-month cooling-off creates avoidable pendency; inconsistent dispensation across courts.

- New Rent Act— confusion about oral leases and jurisdiction leads to forum shopping and delays.

- Archaic CPC provisions enabling delay: Multiple provisions—preliminary vs final decrees in partition suits, 106 rules under Order XXI (execution), rigid timelines like Order VIII Rule 1—allow litigants to drag proceedings despite amendments in 1976 and 2002.

- Pendency not limited to lower courts; Higher judiciary’s slow termination of proceedings adds to systemic backlog. Appeals and interim orders prolong the lifecycle of disputes.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- Procedural rigidity without substantive benefit: Mandatory mediation, cooling-off periods, and multi-stage decrees delay resolution without improving dispute settlement.

- Statutory “gaps” and drafting ambiguities: Rent Act’s ambiguity on oral leases and jurisdiction creates a nebulous system—pushing litigants to civil or commercial courts rather than specialised rent courts.

- Execution as the weakest link: Order XXI’s technicalities allow judgment-debtors to stall the execution of decrees and arbitration awards for years, undermining access to justice.

- Inexperienced judicial officers: Recruiting judges without adequate bar experience leads to poor quality orders and hesitation in decision-making, increasing adjournments and pendency.

- Outdated legal architecture: CPC (1908) and many procedural statutes operate in a litigation environment very different from today, yet reforms have been piecemeal.

Reforms Suggested

- Reduce Clerical Burden on Judges

Create a small “ministerial court” in every district to handle summons, filings, ex parte evidence, and daily listing.

• Let regular courts focus only on hearings and judgments. - Improve Judge Training and Experience

Prefer recruits with some bar experience.

• Give new judges a few months of training at High Court Benches to learn practical judicial work.

• Continuous training in judgment writing and procedure. - Simplify Procedural Laws

Merge preliminary and final decrees in partition suits or make final decree automatic.

• Cut down unnecessary steps in execution (Order XXI) to stop delay tactics.

• Allow flexible timelines for written statements in non-commercial cases. - Fix Problematic Statutory Provisions

Make pre-suit mediation optional where parties have already exchanged notices.

• Allow uniform waiver of six-month cooling-off period in mutual divorce when settlement is clear.

• Remove confusion in the Rent Act by recognising oral leases and clarifying jurisdiction. - Make Execution Faster and Simpler

Require early asset disclosure by defendants.

• Set strict timelines for execution.

• Penalise frivolous objections. - Improve Higher Judiciary’s Role

Dispose appeals within reasonable timelines.

• Restrict frequent adjournments.

• Prioritise final hearings instead of endless interim matters.

Conclusion

India’s lower judiciary suffers not merely from insufficient manpower but from structural inefficiencies, outdated procedures, and inadequate judicial preparation. Real reform lies in freeing judges from clerical burdens, simplifying archaic laws, improving training, and modernising execution processes—turning the judiciary into a system that delivers timely and qualitative justice.

Mains Question

- Pendency in subordinate courts is rooted in procedural rigidity, inadequate training, and legislative design flaws. Discuss how structural reforms in the lower judiciary can address India’s chronic backlog. (250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Hindu

(UPSC GS Paper III – “Environmental pollution and degradation”)

Context (Introduction)

India’s recurring winter smog and year-round pollution in cities like Delhi and Mumbai mirror China’s crisis of the 2000s. China’s rapid improvements—80% of its territory saw better air quality after 2013—offer relevant lessons for India’s struggle.

Main Arguments

- China’s ‘Airpocalypse’ resembled India’s current crisis: Rapid industrialisation, coal-based heating, vehicle emissions, crop burning and unfavourable meteorology caused severe PM2.5 levels. India today faces similar drivers, compounded by winter inversions, stubble burning and biomass fuel use.

- 2006–2013 marked China’s policy shift: The 11th Five-Year Plan recognised pollution as a national priority. The “cadre evaluation system” linked promotions of governors, mayors and officials to pollution reduction—creating strong administrative accountability.

- Forceful industrial regulation: Outdated coal boilers, smelters, chemical units and paper mills were shut; heavy industry was modernised with pollution-control equipment. This targeted high-emission sources responsible for PM2.5.

- Aggressive transition to clean mobility: Cities like Shenzhen fully electrified 16,000 buses by 2017; Shanghai followed. EVs, despite coal-heavy grids, still reduced urban emissions by eliminating tailpipe pollution.

- Multi-pronged control measures (2013–17): Tsinghua University research found that cleaner heating, coal boiler controls, industrial closures and vehicle standards—jointly—led to significant air quality improvement across Chinese cities.

- Caveats and limitations: Top-down pressure led to data manipulation and hidden reopening of factories. China’s air quality standards remain weaker than Western benchmarks. The return to coal investment after the 2021 power shortage risks reversing gains.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- China’s highly authoritarian enforcement model often encouraged officials to falsify pollution datato meet targets, instead of ensuring real on-ground compliance.

- Heavy dependence on coal continues, increasing the risk of rising PM2.5 levels and ground-level ozone despite earlier gains.

- China’s air quality standards themselves are relatively weak, so “improvement” does not always translate into air that is actually safe or comparable to global health norms.

- Centralised governance reduces avenues for legal accountability, unlike India where PILs and courts can hold authorities responsible for environmental failures.

- India faces additional structural challenges—widespread biomass use, uneven access to electricity, and multi-layered federal governance—which make replicating China’s model more complex.

Reforms / Lessons for India

- Continuous, Not Seasonal, Action

China acted year-round; India’s GRAP activates only after AQI crosses limits. India needs 24×7, 365-day implementationof emission control—industrial, vehicular, waste-burning, and construction dust. - Strong Accountability for Pollution Control

• Put clear responsibility on State Pollution Control Boards, municipalities and industrial regulators.

• Link institutional performance to measurable improvements, similar to China’s cadre evaluation system but adapted to democratic structures. - Target Major Emitters First

• Strict control of coal-based industries, brick kilns, and diesel generators.

• Enforce continuous emissions monitoringand credible penalties for non-compliance.

• Phase out outdated industrial units with financial support for clean upgrades. - Cleaner Mobility & Public Transport

- Expand electric buses in major Indian cities (Delhi has begun, but scale is limited).

- Promote EV infrastructure where grid capacity exists.

- Encourage modal shift to metro, buses, cycles through better last-mile connectivity.

- Address Rural Biomass Emissions

• Ensure affordable LPG or clean cooking energyfor all households.

• Strengthen Ujjwala subsidies; improve rural distribution networks. - Tailor China’s Approach to Indian Realities

• China acted after achieving near-universal electricity access; India must balance pollution control with growth needs.

• Use Indian-style legal accountability—PILs, NGT rulings, decentralised monitoring—to supplement executive action. - Invest in Monitoring & Research

• Strengthen air quality stations, satellite measurements and local forecasting models.

• Use real-time data to guide enforcement and public advisories.

Conclusion

China’s experience shows that air quality can improve quickly when political will, clear accountability, strong industrial regulation and clean mobility come together. India’s pathway must be democratic, decentralised and socially inclusive, but drawing upon China’s successes—continuous action, strict enforcement and scientific monitoring—can help India build a cleaner, healthier urban future.

Mains Question

- “China achieved rapid reductions in urban air pollution through strict enforcement, industrial regulation and clean mobility. What lessons can India draw while balancing growth, governance complexity and public health?” (250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Indian Express