Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

- Google’s new AI, Cell2Sentence-Scale 27B (C2S-Scale) finds promising approach for cancer treatment.

About C2S-Scale:

- Nature: The Cell2Sentence-Scale 27B (C2S-Scale) is a 27-billion-parameter foundation model designed to understand the language of individual cells within the body. This enables it to simulate and predict cellular behaviour under various conditions, such as in diseases like cancer.

- Significance: C2S-Scale can generate insights that were previously unrecognized by understanding how individual cells react and interact. This allows researchers to explore new pathways in drug discovery and disease treatment.

- Development: The C2S-Scale is an advanced artificial intelligence (AI) model developed by Google DeepMind and Google Research in collaboration with Yale University and based on the Gemma framework.

- Changes course of medical research: This development marks a significant milestone in medical research by generating new scientific hypotheses, bridging computational predictions with experimental validation.

- Working mechanism:

- The model was trained using large data sets to identify patterns in cell behavior, especially under conditions where immune system responses are low (low levels of interferons), such as in early-stage cancer.

- By analyzing this data, C2S-Scale can generate hypotheses about cellular behavior and suggest potential drug combinations that could trigger immune responses in tumors that are typically hidden from the immune system.

Source:

Category: International Relations

Context:

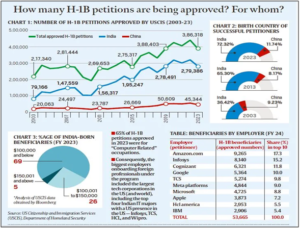

- The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed a lawsuit challenging the Donald Trump administration’s $100,000 fee on new H-1B visa applications.

About H-1B Visa:

- Nature: The H-1B is a non-immigrant visa which allows temporary entry to the US for purposes like tourism, business, work, study, or medical treatment.

- Objective: It allows US-based companies to hire and employ foreign workers for specialty jobs like science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM), and IT (High skills and at least a bachelor’s degree).

- Introduction: It was introduced in 1990 to help US employers address skill shortages when qualified US workers are unavailable.

- Duration: The H-1B visa is valid for three years and can be extended one time for an additional three years. In general, the H-1B is valid for a maximum of six years. There is no limit to the number of H1-B Visas that an individual can have in his or her lifetime.

- Buffer period for reapplication: After this period, the visa holder must either leave the US for at least 12 months before reapplying for another H-1B visa or apply for a Green Card (Lawful Permanent Residency for themselves and their family).

- Eligibility:

- A valid job offer from a U.S. employer for a role that requires specialty knowledge

- Proof of a bachelor’s degree or equivalent experience in that field

- The US employer must show that there is a lack of qualified U.S. applicants for the role.

- Limit: Currently, there is a regular annual cap of 65,000 new H-1B visas each fiscal year. An additional 20,000 visas are available for applicants who hold a master’s degree or higher from a US university.

- Exemptions: Petitions for H-1B visa holders seeking continued employment and those seeking employment at higher education institutions, affiliated nonprofits, or government research organizations are eligible for cap exemption.

- Dominance of Indians: People born in India are the largest beneficiaries accounting for more than 70% of all approved H-1B petitions annually since 2015. People born in China rank second, consistently making up 12-13% of petitions since 2018.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

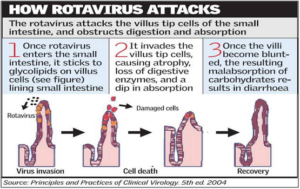

- A recent study on the impact of the indigenous rotavirus vaccine in India found marked reductions in rotavirus-based gastroenteritis in sites across the country.

About Rotavirus:

- Family: Rotavirus is a double-stranded RNA virus genus in the Reoviridae family.

- Contagious: Rotavirus is a contagious disease that spreads easily from child to child.

- Mortality: Rotavirus is a leading cause of severe diarrhoea and death among children less than five years of age. It is responsible for around 10% of total child mortality every year.

- Mode of spread: Rotavirus spreads easily through the fecal-oral route )when a person comes in contact with the feces of someone who has rotavirus and then touches their own mouth). For example, rotavirus can spread when a child with rotavirus doesn’t wash their hands properly after going to the bathroom and then touches food or other objects.

- Symptoms

- Severe diarrhea

- Throwing up

- Dehydration

- Fever

- Stomach pain

- Dosage: World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that the first dose of rotavirus vaccine be administered as soon as possible after 6 weeks of age, along with DTP vaccination (diptheria, tetanus and pertussis).

- Inclusion in National Schedules: WHO has recommended the inclusion of rotavirus vaccine in the National Schedules of the countries where under five mortality due to diarrhoeal diseases is more than 10%.

- Vaccines available: Currently, two vaccines are available against rotavirus:

- Rotarix (GlaxoSmithKline): is a monovalent vaccine recommended to be orally administered in two doses at 6-12 weeks.

- Rota Teq (Merck) is a pentavalent vaccine recommended to be orally administered in three doses starting at 6-12 weeks of age.

Source:

Category: Government Schemes

Context:

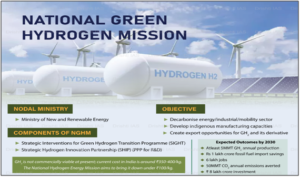

- In a move towards greener public transport, Pune has begun trials of a hydrogen fuel-powered bus under the Centre’s National Green Hydrogen Mission.

About National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM):

- Launch: India launched the National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM) in January 2023 with the budget outlay of Rs. 19,744 crore.

- Ministry: The Ministry of New & Renewable Energy (MNRE) is tasked with implementing the scheme.

- Objective: The mission’s primary aim is to establish India as a global hub for the production, utilisation, and export of green hydrogen and its derivatives. The main target of the scheme to achieve a production capacity of 5 million tonnes per annum of Green Hydrogen in the country by the year 2030.

- Major components of the scheme:

- Strategic Interventions for the Green Hydrogen Transition Programme (SIGHT): SIGHT will incentivise the domestic manufacturing of electrolysers and the production of green hydrogen.

- Green Hydrogen Hubs: The mission will identify and develop states and regions into Green Hydrogen Hubs, fostering large-scale production and utilization.

- Hydrogen Valley Innovation Cluster (HVIC): The Department of Science and Technology has initiated Hydrogen Valley Innovation Clusters to foster innovation and promote the green hydrogen ecosystem in India.

- Dedicated portal: Under NGHM a dedicated portal was launched to provide information on the mission and steps for developing the green hydrogen ecosystem in India.

- Guidelines: India has also released scheme guidelines for the use of Green Hydrogen in steel, transport, and shipping sectors.

- Expected Outcomes by 2030:

- A green hydrogen production capacity of at least 5 MMT per year.

- An addition of approximately 125 GW of renewable energy capacity.

- Over Rs. 8 lakh crore in total investments.

- Creation of over six lakh jobs.

- A reduction in fossil fuel imports exceeding Rs. 1 lakh crore.

- Averting nearly 50 MMT of annual greenhouse gas emissions.

Source:

Category: History and Culture

Context:

- In a recent interview, the Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India discussed reforms for the complete revival of the organisation’s excavation policies.

About Archaeological Survey of India (ASI):

- Nature: ASI is the premier organization for the archaeological research and protection of the cultural heritage of the nation.

- Foundation: ASI was founded in 1861 by Alexander Cunningham (the first Director-General of ASI). He is also known as the “Father of Indian Archaeology.”

- Statutory body: After independence, it was established as a statutory body under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958 (AMASR Act).

- Ministry: It works under the Ministry of Culture.

- Coverage: It administers more than 3650 ancient monuments, archaeological sites and remains of national importance.

- Works: Its activities include carrying out surveys of antiquarian remains, exploration and excavation of archaeological sites, conservation and maintenance of protected monuments etc.

- ASI Circles:

- For the maintenance of ancient monuments and archaeological sites and remains of national importance the entire country is divided into 36 Circles.

- These carry out archaeological fieldwork, research activities and implement the various provisions of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (AMASR) Act, 1958 and Antiquities and Art Treasures Act 1972.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(GS Paper II – India and its Neighbourhood Relations)

Context (Introduction)

The 75th anniversary of India–China diplomatic ties and the 80th anniversary of the UN coincide with a shifting world order. The 2025 Tianjin SCO Summit highlights renewed efforts by Asia’s two major powers to reform global governance through the Global Governance Initiative (GGI).

Background of India–China Relations

- India established diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China on April 1, 1950, becoming one of the earliest countries to recognize it.

- The 1954 Panchsheel Agreement laid down the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence — mutual respect, non-interference, and equality — which continue to guide relations.

- The early phase of fraternity, symbolized by “Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai,” ended with the 1962 war and left deep strategic distrust.

- Normalization began after Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s 1988 visit, leading to border agreements (1993, 1996, 2005) and institutional dialogues through BRICS, SCO and G-20.

- From 2014 to 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping met 18 times — in BRICS, G-20, and bilateral summits — showing sustained engagement despite frictions.

- Economic relations deepened, with trade crossing USD 115 billion (2024-25), though India’s deficit remains large.

- After the Galwan Valley clash (2020), military disengagements and the 2024 Kazan meeting restored partial normalcy, followed by the 2025 Tianjin SCO Summit.

Main Arguments

- Shared Historical Responsibility: Both nations, representing one-third of humanity, share responsibility for promoting peace, development, and the rejuvenation of developing countries.

- Xi–Modi Engagement: Leaders have emphasized mutual respect, peaceful borders, and resumption of direct flights — signalling a “return to a positive trajectory.”

- Global Governance Initiative (GGI): Introduced by China at Tianjin, the GGI aims to address the deficit in global governance and build a system that is more inclusive, democratic, and development-oriented.

- Five Principles of GGI:

- Sovereign Equality – All nations, big or small, should participate as equals, respecting each other’s development paths.

- Rule of Law – Uphold UN Charter principles without double standards or hegemonic interpretation.

- Multilateralism – Global affairs must be decided collectively through institutions like the UN, not bilateral power politics.

- People-Centric Approach – The ultimate goal of global governance is the well-being of the people through development, security, and dignity.

- Result-Oriented Action – Focus on practical solutions to climate change, development gaps, and inequality.

- Reform Without Disruption: GGI does not seek to replace the UN system but to make it more effective, inclusive, and adaptive to new challenges.

- Complementary Visions: China’s GGI and India’s G20 theme (“One Earth, One Family, One Future”) share a human-centric development ethos.

- Asia as Driver of Change: The rise of Asia and Eurasia, coupled with the West’s relative decline, makes India–China cooperation crucial for multipolarity.

- Institutional Synergy: Through SCO and BRICS, both nations can coordinate on issues like terrorism, climate action, digital economy, and reform of global financial architecture.

- South-South Leadership: The two can jointly champion the voice of developing countries for a fairer distribution of public goods such as technology and climate finance.

Challenges in the Relationship

- Border Disputes: Despite dialogue mechanisms, the LAC remains undemarcated; trust deficit after Galwan (2020) persists.

- Strategic Competition: India’s partnership in QUAD and Indo-Pacific frameworks is seen by China as containment; India views the BRI as violating sovereignty via CPEC.

- Economic Asymmetry: Trade imbalance of over USD 80 billion and dependence on Chinese inputs (APIs, electronics) create strategic risks.

- Ideological Differences: China’s state-centric model and India’s democratic pluralism limit policy alignment.

- Regional Influence Clash: Rivalry for influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean complicates trust.

- Institutional Constraints: Bilateral dialogue mechanisms (SR Talks, WMCC) are consultative but lack binding implementation capacity.

- Public Perception Gap: Negative media portrayals and border nationalism hinder people-to-people trust.

- Global Polarisation: US-China rivalry pressures India to balance strategically, limiting space for independent cooperation.

Way Forward

- Institutionalise Dialogue: Create an India–China Strategic Communication Mechanism on Global Governance within the SCO/BRICS framework.

- Peaceful Borders First: Strengthen hotline communication, joint patrol protocols, and confidence-building measures for LAC stability.

- Economic Rebalancing: Encourage co-production and investments in pharmaceuticals, renewables, and digital connectivity to reduce trade asymmetry.

- Regional Collaboration: Align GGI with India’s SAGAR (Safety and Growth for All in the Region) and Act East Policy to promote cooperative security.

- Multilateral Leadership: Push for UN Security Council reform, revitalise WTO negotiations, and enhance climate finance for developing countries.

- People-to-People Bridges: Resume direct flights, academic exchanges, and city-to-city partnerships for cultural reconnection.

- Joint Global Initiatives: Co-sponsor programmes on digital ethics, pandemic preparedness, and AI governance to showcase responsible Asian leadership.

- Balanced Multipolarity: Pursue “cooperative competition” — managing disputes while expanding shared interests in global issues.

Conclusion

India–China relations embody both friction and opportunity. Their ability to transform competition into collaboration will determine whether the 21st century truly becomes an Asian century. By advancing inclusive multilateralism through initiatives like the GGI, the two civilizations can shape a more democratic, rule-based, and equitable world order.

Mains Question

- What are the key principles of the Global Governance Initiative (GGI) proposed at the 2025 Tianjin SCO Summit? Examine how these principles align with India’s vision for a multipolar and equitable world order. (15 marks, 250 words)

Source: The Hindu

(GS Paper I – Economic Geography: Important Crops and Major Agricultural Products of the World)

Context (Introduction)

India is the world’s second-largest producer of tea and the largest producer of black tea, yet its global brand presence remains weak. Despite its cultural centrality and export potential, Indian tea faces policy, structural, and marketing challenges.

Background: India’s Tea Legacy

- Origin and Spread: India and China are the original homes of tea cultivation. Tea was first commercialised under British colonial rule after Robert Bruce discovered wild tea in Assam in 1823.

- Institutional Framework: The Tea Board of India (est. 1953) regulates the sector, while auction systems like J. Thomas & Co. in Kolkata (since 1861) continue to determine pricing.

- Production Statistics: India produced around 1,285 million kg in 2024, second to China’s 3,700 million kg. However, only 20% is exported, with most consumed domestically.

- Global Image: While Sri Lanka and Kenya have marketed distinctive national brands (“Ceylon Tea” with the Lion logo), Indian tea is mostly exported as unbranded blends, losing identity and value.

- Major Tea Regions: Assam, West Bengal (Darjeeling, Dooars, Terai), Tamil Nadu (Nilgiris), and Kerala form India’s tea heartlands, employing over 1 million workers.

Main Arguments: Why Indian Tea Lacks Global Brand Value?

- Overreliance on Bulk Exports: Nearly 90% of Indian tea is sold in bulk for blending (e.g., “English Breakfast” or “Earl Grey”), erasing India’s distinct regional identity.

- Auction Dependency and Policy Rigidities: The Tea Board mandates that 50% of produce be sold via public auctions, discouraging innovation and direct marketing. In contrast, coffee growers gained flexibility after the Coffee Board’s auction system ended in 1996.

- Weak Branding and Marketing: Few Indian brands (Tata’s Tetley, Makaibari, Cha Bar) operate globally. There’s little coordinated brand promotion unlike Sri Lanka’s state-backed campaigns since the 1980s.

- Structural Problems in Production: Over 50% of production now comes from small growers (<25 acres) who fall outside the Plantation Labour Act. This leads to uneven quality, low wages, and weak compliance with sustainability standards.

- Domestic Consumption Patterns: Tea is viewed as a household necessity rather than a lifestyle product. Coffee, in contrast, became aspirational through cafés and urban branding (Café Coffee Day, Starbucks).

- Labour and Environmental Challenges: Poor working conditions, labour unrest, and climate change–induced yield variations have led to estate closures in Darjeeling, Nilgiris, and Assam.

- Market Competition: Kenya and Vietnam have captured significant export shares due to mechanised production and low costs. Nearly half of tea consumed in the UK is now Kenyan.

Challenges and Constraints

- Institutional Inertia: The Tea Board’s dual role as regulator and marketer creates bureaucratic inefficiency.

- Fragmented Industry: Over 2,000 small growers operate informally, limiting economies of scale.

- Lack of Innovation: Traditional processing and packaging limit value addition.

- Price Volatility: Auction-determined prices fluctuate, making planning difficult for small estates.

- Climate Vulnerability: Erratic rainfall and rising temperatures affect yields in Assam and Darjeeling.

- Decline of Traditional Markets: The collapse of the Soviet Union, once India’s largest buyer, disrupted long-standing trade patterns.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Branding and Geographical Indications (GI): Promote Darjeeling, Assam, and Nilgiri teas under protected GI tags with strict quality standards, similar to Sri Lanka’s Lion logo system.

- Auction Reforms: Allow direct marketing and e-commerce sales for producers; create a transparent digital auction model with quality certification.

- Labour and Sustainability Standards: Integrate small growers into formal systems; link wages and certification (Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance) to export incentives.

- Marketing and Value Addition: Launch a “Brand India Tea” campaign showcasing tea as both heritage and health drink. Encourage boutique stores, tourism-linked cafés, and wellness branding.

- Diversification and Innovation: Promote tea-based wellness products, flavoured teas, and ready-to-drink (RTD) beverages targeting youth markets globally.

- Institutional Support: Restructure the Tea Board as a Tea Development and Export Promotion Authority, focusing on R&D, marketing, and global partnerships.

- International Collaboration: Collaborate with global tea research institutes to improve varieties resistant to climate stress and pests.

Conclusion

Tea is not merely an agricultural crop in India—it is a cultural and economic symbol. For India’s “chai” to achieve its global potential, the sector must move beyond colonial-era systems toward a brand-led, innovation-driven, and sustainable model. Like coffee, Indian tea needs a new story — one rooted in authenticity, modernity, and pride in its origins.

Mains Question

- What factors have prevented Indian tea from emerging as a global brand despite being the world’s second-largest producer? Suggest reforms to enhance its competitiveness. (15 marks, 250 words)

Source: The Hindu