Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: Environment and Ecology

Context:

- In a first since the Cheetah Reintroduction Project in the country, an Indian-born cheetah has given birth to five cubs at the Kuno National Park.

About Kuno National Park:

- Location: It is located in the Sheopur district of Madhya Pradesh. It is nestled near the Vindhyan Hills.

- Establishment: It was declared a wildlife sanctuary in 1981, upgraded to a national park in 2018.

- Nomenclature: It derives its name from the meandering Kuno River (one of the main tributaries of the Chambal River), which flows from south to north and divides the park into two sections.

- Area: It covers an area of 750 sq.km.

- Uniqueness: It was selected under the ‘Action Plan for Introduction of Cheetah in India.’ A total of 20 cheetahs were introduced in Kuno National Park (NP), eight from Namibia in September 2022, followed by 12 more from South Africa in February 2023 under the Cheetah Project.

- Potential to carry all four big cats: The Kuno has the potential to carry populations of all four of India’s big cats. The tiger, the leopard, the Asiatic lion, and also the cheetah all four of which have coexisted within the same habitats.

- Flora: Kuno National Park has a rich floral diversity with more than 129 species of trees. These tropical dry deciduous forests mainly consist of Anogeissus pendula (Kardhai), Senegalia catechu (Khair), Boswellia serrata (Salai), and associated flora.

- Fauna: The protected area of the forest is home to the jungle cat, Indian leopard, sloth bear, Indian wolf, striped hyena, golden jackal, Bengal fox, and dhole, along with more than 120 bird species.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

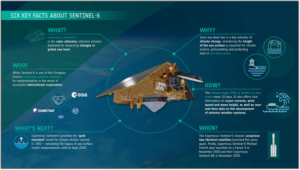

- Sentinel-6B was launched recently from the Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

About Sentinel-6B:

- Nature: It is a joint mission between the United States’ NASA and NOAA, and the European Space Agency. It is the latest in a series of satellites launched since the 1990s, mainly by NASA, to measure the sea-level changes from space.

- Objective: It is an ocean-tracking satellite which will measure the rising sea levels and its impacts on the planet. It will provide primary sea level measurements down to approximately an inch from over 90% of all the oceans.

- Launch: It was lunched aboard a SpaceX Falcon-9.

- Continues legacy of Sentinel-6: It is set to carry forward the legacy of Sentinel -6 Michael Freilich, launched in November 2020.

- Orbiting speed: It will orbit Earth at a speed of 7.2 km per second, completing one revolution every 112 minutes. It is expected to spend the next 5.5 years in orbit.

- Coverage: It maps more than 90% of the world’s ice-free oceans every 10 days.

- Components: It consists of six onboard science instruments. It has two fixed solar arrays, plus two deployable solar panels, and will travel in a longitude direction around Earth in a non-Sun-synchronous orbit.

- Significance: It observes Earth’s oceans, measuring sea levels to improve weather forecasts and flood predictions. It also safeguards public safety, benefits commercial industry, and protects coastal infrastructure.

Source:

Category: History and Culture

Context:

- Recently, raulane festival, a unique and sacred winter festival was celebrated in Himachal Pradesh’s Kinnaur district.

About Raulane Festival:

- Location: It is a traditional festival celebrated in Kalpa, Kinnaur district, Himachal Pradesh, in winter or early spring.

- History: This ancient festival is believed to be around 5,000 years old. It honours celestial fairies, known as Saunis, said to be radiant and gentle beings.

- Faith: Locals believe that the Saunis protect villagers during harsh winters by offering warmth and guidance.

- Symbolic marriage ceremony: During the festival, two men symbolically “marry” and become vessels for the Saunis, embodying a divine couple, the Raula (groom) and the Raulane (bride).

- Use of heavy costumes and masks: They get dressed in heavy woollen robes, ornaments and unique face masks.

- Ritual dance: They also perform a slow, meditative dance at the Nagin Narayan Temple, and the whole community joins in.

- Significance: The Raulane festival preserves ancient Himalayan culture and traditions, with villagers coming together to honour their protectors.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

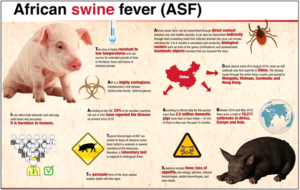

- Recently, Assam Government banned the movement of live pigs in the State to arrest the spread of African swine fever.

About African Swine Fever (ASF):

- Nature: The African swine fever is a highly contagious and hemorrhagic viral disease affecting pigs and wild boar.

- Not zoonotic: The disease does not infect humans (not zoonotic) or other livestock species.

- Fatality: ASF causes a destructive effect on piggery due to high morbidity and mortality (up to 90-100%).

- Spread: Originally found throughout sub-Saharan Africa, ASF is now prevalent in many countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

- First case in India: India notified the first outbreak of ASF virus in January, 2020 in the Northeastern States of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh.

- Transmission: The virus is highly resistant in the environment, meaning that it can survive on clothes, boots, wheels, and other materials. Infection can also occur through direct contact between pigs or boars.

- Symptoms: The clinical symptoms can look very much like those of classical swine fever such as fever, lack of appetite, inflamed eye mucous membranes, red skin, diarrhea, and vomiting.

- Prevention: Currently, there is no treatment or vaccine available against ASF, so prevention by adopting strict biosecurity measures, such as culling the animals, is the only way to prevent ASF.

- Listed in OIE’s Terrestrial Animal Health Code: It is listed in the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE)’s Terrestrial Animal Health Code.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

- Union Minister Dr. Jitendra Singh launches India’s first indigenous “CRISPR” based gene therapy named ‘BIRSA 101’ for Sickle Cell Disease.

About BIRSA 101:

- Nomenclature: The therapy has been named Birsa-101 in honour of the tribal leader Birsa Munda.

- Uniqueness: It is India’s first indigenous CRISPR-based gene therapy, designed to treat Sickle Cell Disease (SCD).

- Development: It is developed by the CSIR-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (IGIB) in partnership with the Serum Institute of India (SIIPL) for technology transfer, scale-up, and affordable national deployment.

- Objective: It aims to support India’s mission of becoming Sickle Cell–Free by 2047, as envisioned by the Prime Minister.

- Use of CRISPR Technology: It utilizes the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool to correct the genetic mutation causing Sickle Cell Disease.

- Affordable: It is priced significantly lower than global CRISPR treatments, making it more accessible to the poorest populations.

- Mechanism: It edits defective genes inside the patient’s cells and corrects the mutation responsible for producing sickle-shaped red blood cells, thereby enabling normal haemoglobin production.

- One time infusion: The therapy has to be given as a one-time infusion, after which the body should start producing normal red blood cells instead of sickle-shaped ones.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(GS Paper II – Federalism, Centre–State Relations, Devolution of Powers, Finance Commission)

Context (Introduction)

Escalating tensions between the Centre and various Opposition-ruled States over GST decisions, fiscal transfers, CSS funding, and use of cesses have revived concerns about whether single-party political dominance is accelerating a drift toward centralisation, weakening India’s federal equilibrium.

Main Arguments

- Shift from coalition-based accommodation to centralised dominance: The 1990s–2000s saw institutional negotiation between Centre and States. After 2014, single-party dominance has reshaped federal bargaining, reducing avenues for deliberative decision-making.

- Weakening of intergovernmental institutions: The abolition of the Planning Commission removed a key coordination platform. GST Council functioning has faced criticisms for unilateral decision-making contrary to early cooperative norms.

- Horizontal fiscal imbalance concerns: Southern States argue that Finance Commission formulas (population, inverse-income criteria) structurally favour northern States, ignoring spatial inequality and demographic transitions.

- Rising centralisation through fiscal tools: Cesses and surcharges — outside the divisible pool — have steadily risen, constraining State fiscal space. CSS allocations are increasingly determined by the Centre without consistent consultation.

- Changing political economy and weakened regional autonomy: Declining regional capital, competitive populism, and limited job creation alter States’ bargaining capacity vis-à-vis the Centre.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- Shrinking State autonomy over finances: With cesses rising and GST limiting indirect tax powers, States face weakened control over revenues.

- Erosion of trust and “good faith” obligations: States allege unilateral Centre-driven decisions in GST disputes, fund releases, and CSS design.

- Institutional imbalance post-Planning Commission: No equivalent body now supports coordinated long-term State–Centre developmental planning.

- Deepening structural spatial inequality: Fiscal formulas do not fully address disparities in growth, migration, wages, and demographics.

- Changing nature of federal coalitions: Unlike earlier coalitions dependent on regional parties, current alliances do not prioritise federal bargaining.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Strengthen Intergovernmental Institutions

- Establish a permanent Inter-State Council Secretariat to institutionalise federal dialogue.

- Operationalise regular Zonal Council meetings with statutory follow-up, as recommended by the Punchhi Commission.

- Revisit the role of NITI Aayog to grant it fiscal and planning powers, restoring cooperative planning functions earlier performed by the Planning Commission.

- Reform Fiscal Federalism

- Limit excessive use of cesses and surcharges, aligning with 15th FC observations on improving the divisible pool.

- Adopt a balanced horizontal devolution formula that acknowledges demographic achievements (southern States) while retaining redistribution — an approach suggested by multiple Finance Commissions.

- Implement independent fiscal councils at the Union and State levels, as recommended by the Rangarajan Committee, to depoliticise fiscal assessments.

- Enhance GST Council Federalism

- Strengthen the Council’s dispute resolution mechanism (never operationalised), as envisaged in Article 279A.

- Return to consensus-based decision norms, consistent with the cooperative spirit recommended during GST design.

- Ensure predictable GST compensation mechanisms, following expert recommendations for a “GST Stabilisation Fund.”

- Rebalance Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS)

- Rationalise the number of CSS and expand flexible components for State-specific adaptation.

- Adopt transparent formula-based fund releases to reduce political discretion.

- Shift monitoring from the Ministry of Finance to a broad-based federal body (as suggested by ARC).

- Address Structural Spatial Inequality

- Create an Equalisation Grant Framework for lagging regions to reduce spatial disparities (Rajan Committee).

- Encourage labour-intensive regional growth via wage reforms, regional capital incentives, and targeted migration policy.

- Strengthen institutional parity by investing in poorer northern districts — a long-standing expert recommendation.

Conclusion

India’s federalism is undergoing a stress test. While redistribution remains a constitutional principle, weakened institutional forums, unilateral fiscal decisions, and centralised political incentives have generated friction. Strengthening cooperative federalism requires transparent fiscal norms, empowered institutions, and a renewed commitment to balancing national cohesion with regional autonomy.

Mains Question

- Is cooperative federalism weakening under conditions of single-party dominance? Evaluate recent Centre–State tensions and suggest reforms based on major committee and commission recommendations.(250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Hindu

(GS Paper II – Polity: Governor’s Role, Centre–State Relations, Separation of Powers, Judicial Review)

Context (Introduction)

In a landmark advisory opinion on the Governor’s powers under Articles 200 and 201, the Supreme Court has ruled that it cannot impose timelines for granting assent, rejected the idea of “deemed assent,” and reaffirmed both institutional autonomy and constitutional balance between executive and judiciary.

Main Arguments

- Court rejects judicially imposed timelines: The SC unanimously held that prescribing rigid timeframes for Governors or the President would blur the line between judicial interpretation and judicial legislation. Article 200 uses “as soon as possible,” deliberately without fixed limits.

- No ‘deemed assent’ under the Constitution: The Court overturned the earlier April verdict that had allowed “deemed assent.” It held that courts cannot create constitutional fictions or substitute executive functions under Article 142.

- Three constitutionally valid options for the Governor: The Governor may (a) grant assent, (b) return the Bill for reconsideration, or (c) reserve it for the President. There is no fourth option of withholding assent indefinitely or refusing to act.

- Governor’s discretion exists but is limited: Under Articles 200 and 163, the Governor exercises discretion in assent matters and is not bound by the Cabinet’s advice. However, the discretion cannot be used to paralyse the legislative process.

- Judicial review remains available only in ‘glaring circumstances’: While merits of the Governor’s decision are non-justiciable, prolonged, unexplained, indefinite inaction can invite a limited mandamus directing the Governor to act — without dictating the outcome.

Criticisms / Drawbacks

- Risk of continued constitutional bottlenecks: With no timelines prescribed, States fear that Governors may still delay assent, potentially affecting governance and legislative effectiveness.

- Subjective satisfaction remains outside judicial scrutiny: The Court reaffirmed that the reasons behind the Governor’s or President’s decisions are not open to merits review, leaving limited recourse for States aggrieved by political misuse.

- Advisory opinion complicates implementation: As this is not a judicial verdict but an Article 143 advisory, earlier High Court or SC decisions may still be cited, creating interpretational uncertainty.

- Debates on justiciability remain unresolved: The Court’s view that subjective satisfaction is non-justiciable differs from precedents such as review of President’s Rule, potentially leaving doctrinal questions open.

- Federal friction may persist: The ruling recognises delayed assent as a constitutional problem but addresses it only procedurally, not substantively, leaving space for continued Centre–State tensions.

Reforms and Way Forward

- Clarify Governor’s discretionary boundaries (Sarkaria & Punchhi Commissions)

- Codify limited discretionary areas; require Governors to act primarily on Cabinet advice except in constitutionally specified situations.

- Mandate written reasons when Bills are returned, ensuring transparency and reducing arbitrariness.

- Strengthen Centre–State consultation mechanisms (Punchhi Commission)

- Activate the Inter-State Council as a regular forum for resolving disputes involving Governors.

- Institutionalise structured consultation between Governor’s Secretariat and State governments in legislative matters.

- Reform appointment and tenure processes (ARC & Punchhi)

- Create a neutral, bipartisan Governor Appointment Committee, reducing perceptions of partisan use of gubernatorial offices.

- Ensure fixed, secure tenure to prevent political pressure.

- Improve constitutional federal functioning (NCRWC & ARC)

- Establish clear guidelines for Governor’s assent functions, similar to model codes proposed by NCRWC, ensuring predictable interactions.

- Develop a federal oversight mechanism to monitor delays in assent, without compromising discretion.

- Strengthen judicial review architecture (NCRWC)

- Allow procedural review (not merits review) of gubernatorial delays, aligning with the Court’s “glaring circumstances” test.

- Maintain judicial restraint while reinforcing accountability frameworks.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s advisory opinion reaffirms constitutional boundaries:

- Courts cannot legislate timelines, cannot confer “deemed assent,” and cannot review the merits of gubernatorial decisions.

- By preserving the limited space for judicial intervention against prolonged inaction, the Court ensures balance between executive discretion and constitutional functioning.

- The path ahead lies in implementing long-standing committee recommendations that professionalise the Governor’s office, deepen federal consultation, and strengthen transparency in the assent process.

Mains Question

- How does the Supreme Court’s recent advisory opinion redefine the constitutional limits of the Governor’s powers under Articles 200 and 201? Discuss its implications for federalism and outline committee-recommended reforms to strengthen the assent process.(250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Indian Express