Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: Environment and Ecology

Context:

- To promote tourism and wildlife conservation, Mukundra Hills Tiger Reserve recently launched a poster and trailer of a documentary entitled “Enchanting Mukundra.”

About Mukundra Hills Tiger Reserve:

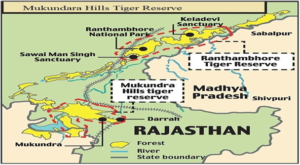

- Location: It is spread across 4 districts of Rajasthan- Bundi, Kota, Jhalawar & Chittorgarh. It was once a hunting preserve belonging to the Maharaja of Kota.

- Other names: It is also known as the Darrah Wildlife Sanctuary.

- Establishment: It was declared a Wildlife Sanctuary in 1955. It was notified as a National Park in 2004. And, it was declared a Tiger Reserve in 2013, becoming Rajasthan’s third tiger reserve (after Ranthambore and Sariska).

- Boundaries: It is situated in a valley formed by two parallel mountains, viz. Mukundra and Gargola.

- Components: It encompasses the area of Mukandra National Park, Darrah Sanctuary, Jawahar Sagar Sanctuary, and part of Chambal Sanctuary (from Garadia Mahadev to Jawahar Sagar Dam), forming its core/critical tiger habitat.

- Connectivity: It is strategically located between Ranthambore and Madhya Pradesh’s Kuno National Park, making it a vital corridor for tiger movement.

- Rivers: It is located on the eastern bank of the Chambal River. And, it is traversed by four rivers- Chambal, Kali, Ahu, and Ramzan.

- Vegetation: It primarily comprises of dry deciduous forests.

- Flora: It includes Kala Dhok, or Kaladhi, is the predominant species, along with Khair, Ber, Kakan, Raunj, etc.

- Fauna: The important fauna includes Leopard, Sloth bear, Nilgai, Chinkara, Spotted Deer, Small Indian Civet, Toddy Cat, Jackal, Hyena, Jungle Cat, Common Langur, etc. The common reptiles and amphibians are Pythons, Rat Snake, Buff-striped keelbacks, Green keelback, crocodiles, Gharial, Otter, and Turtles.

Source:

Category: Defence and Security

Context:

- Recently, DRDO successfully completed the User Evaluation Trials of Next Generation Akash missile (Akash-NG) system.

About Akash-NG Missile System:

- Nature: Akash Next Generation (Akash-NG) is a state-of-the-art surface-to-air missile (SAM) defence system.

- Development: It was developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and produced by Bharat Dynamics Limited (BDL).

- Objective: It is designed to protect vulnerable areas and points from air attacks.

- Legacy: It succeeds the original Akash missile system, which has been operational with the Indian Air Force since 2014 and the Army since 2015.

- Weight: The next-generation variant is lighter, weighing approximately 350 kilograms compared to the original’s 720 kilograms.

- Advanced features: It features an indigenously developed Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA), multi-function radar and an Active Radio Frequency (RF) Seeker for high precision.

- Range: It is designed to engage multiple targets simultaneously, with a range of up to 30 km and an altitude of 18 km.

- Firing rate: It has the ability to engage up to 10 targets simultaneously, with a firing rate of one missile every 10 seconds.

- Speed: It can reach speeds up to Mach 2.5.

- Propulsion: It uses a dual-pulse solid rocket motor, which is lighter and more efficient than the older ramjet engine.

- Deployment: The system can also be deployed in various configurations, including mobile and fixed installations.

- Indigenization: It reflects the “Atmanirbhar Bharat” initiative, with nearly all subsystems, including the seeker and command-and-control units, being developed in-house.

- Enhanced Mobility: The system is canisterized, meaning it is stored in specialized compartments that improve shelf life and allow for rapid deployment across different terrains.

Source:

Category: History and Culture

Context:

- Recently, the Supreme Court declined urgent hearing of a plea against the practice of offering a ‘Chadar’ by the Prime Minister at the Dargah of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti.

About Khwaja Moinuddin Chisti:

- Early Life: He was born in 1141 CE in Sijistan (modern-day Sistan, Iran). He was later orphaned at age 14 and turned to spirituality after a meeting with the mystic Ibrahim Qandozi. He was a very important Sufi saint.

- Other names: People often call him Gharīb Nawāz, which means ‘Benefactor of the Poor’ (for his service to the needy).

- Education: He studied Islamic theology in the famous learning centres of Samarkand and Bukhara.

- Spiritual Lineage: A follower of Sunni Hanafi theology, he became the disciple of Hazrat Khwaja Usman Harooni, who later initiated him into the Chishti order.

- Arrival in India: He arrived in India around 1192 CE, coinciding with the Second Battle of Tarain. He finally settled in the city of Ajmer during the reign of Sultan Iltutmish in Delhi and Prithviraj Chauhan in Ajmer.

- Significance: He is famous for bringing the Chishti Order of Sufism to India. He preached love, tolerance, charity, and detachment from materialism, and established a Khanqah in Ajmer to serve the poor.

- Prominent disciples: His legacy was carried forward by notable saints like Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki (Delhi), Baba Farid (Punjab), and Nizamuddin Auliya (Delhi).

- Dargah: After his death in 1236 CE, Moinuddin Chishti was buried in Ajmer. His tomb is visited by people of all faiths and it is now known as the Dargah Sharif, or the Ajmer Sharif Dargah.

- Architectural style of tomb: The architectural style of Dargah Sharif purely reflects the Mughal style of architecture. All Mughal rulers from Humayun to Shah Jahan have made modifications in the structure.

Source:

Category: Society

Context:

- A total of 17 families (all from Paliyar tribe) in Dindigul district have petitioned the Dindigul Collector to develop their existing settlement as a formal village.

About Paliyar Tribe:

- Location: They are an indigenous tribal community primarily found in the hilly regions of Tamil Nadu and Kerala.

- Nomenclature: Historically, the Paliyars were spread all over the Dindigul district and the Sirumalai Palani hills, adjacent to the Western Ghats. As they inhabited the Palani hills, they were known as Panaiyars.

- Other names: They are and have been known by multiple names, such as the Paliyans, Pazhaiyarares, and Panaiyars.

- Language: They primarily speak a dialect related to Tamil, reflecting their Dravidian linguistic heritage.

- Occupation: Traditionally, the Paliyars were hunters and gatherers, residing in the forests of the Western Ghats. Presently, they have transformed into traders of forest products, food cultivators, and beekeepers, with some working intermittently as wage labourers, mostly on plantations.

- Significance: They are recognized for their extensive knowledge and traditional practices pertaining to the use of medicinal plants.

- Society: Palliyars have small communities called kudis, sometimes living in caves or mud shelters.

- Burial practice: The Paliyar tribes never burned the dead bodies. They had the customary practice of burying the dead bodies in an area near to their residential area on the western side.

- Religious beliefs: They worship nature-based spirits like Vanadevadai and the deity Karuppan. They have a special ceremony to invoke rain and protect the forest spirits.

- Festivals: Their festivals centre around agricultural gratitude, ancestor worship, and nature, with key events being Paliya Ulsavam, Mazhai Pongal, and Masimagam. These involve nature-based rituals, dancing, and music.

Source:

Category: Government Schemes

Context:

- Recently, NCW launched SHAKTI Scholars Young Research Fellowship programme, inviting applications to undertake policy-oriented research on issues affecting women.

About Shakti Scholars Young Research Fellowship:

-

- Nature: It is a six-month program aimed at supporting emerging scholars in researching women’s issues in India.

- Launched by: It is an initiative of the National Commission for Women.

- Duration: The fellowship lasts for six months.

- Objectives:

-

-

- To encourage research on women’s issues from a multidisciplinary perspective.

- To promote academic and policy-oriented studies that contribute to gender equality, safety, and empowerment.

- To provide opportunities for young scholars to engage in meaningful research that can support the Commission’s mandate

-

- Eligibility:

-

- Academic: Must hold at least a graduate degree; preference is given to those completed or pursuing Masters, M.Phil., or Ph.D. in relevant fields.

- Nationality & Age: The fellowship is open to Indian citizens aged between 21 and 30 years who hold at least a graduation degree from a recognised institution.

- Financial Support: Selected candidates will receive a research grant of Rs 1 lakh to undertake a six-month study.

- Research areas: These include women’s safety and dignity, gender-based violence, legal rights and access to justice, cyber safety, implementation of the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (POSH) framework ETC.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(UPSC GS Paper III – Indian Economy: Industrialisation, Growth, Employment, Inequality)

Context (Introduction)

Despite beginning the 20th century at income levels comparable to China and South Korea, India’s manufacturing sector has stagnated, limiting job creation, productivity growth and broad-based income expansion.

Current Status of Manufacturing in India (with data)

- Low and Stagnant GDP Share: Manufacturing contributes ~15% of India’s GDP (World Bank, 2023), compared to ~27% in China and ~25% in South Korea during their peak industrialisation phases.

- Weak Employment Absorption: As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2022–23), manufacturing employs only ~11.6–12% of India’s workforce, far below East Asian peers during their growth phase.

- Services-Dominated Growth: I ndia’s services sector contributes over 55% of GDP but employs a much smaller share of workers, leading to jobless or low-quality employment growth.

- Rising Inequality: Oxfam (2023) notes that the top 10% in India hold over 77% of national wealth, reflecting growth without mass employment or wage gains.

Reasons for Manufacturing Underperformance

- Public Sector Wages and ‘Dutch Disease’ Effect: Economist Arvind Subramanian argues that relatively high government salaries raised economy-wide wages and prices. Manufacturing firms, with lower productivity, could not match these wages, making Indian manufacturing less competitive.

- Real Exchange Rate Pressure: Higher domestic prices increased imports and reduced price competitiveness of exports, even without sharp nominal rupee appreciation.

- Cheap Labour Trap: India’s abundant labour reduced incentives for firms to invest in automation and productivity-enhancing technology.

- Evidence from ASI: The Annual Survey of Industries (2022–23) shows fixed capital grew by 10.6%, while employment grew only 7.4%, with capital per worker rising to ₹23.6 lakh, indicating capital deepening without mass job creation.

Why High Wages Did Not Trigger Innovation

- Missed ‘Induced Innovation’ Pathway: In countries like Britain, Germany and South Korea, high wages pushed firms to innovate. In India, manufacturing failed to respond similarly.

- Stagnant Private Sector Wages: Entry-level salaries in IT and manufacturing-linked services have shown minimal real growth since the early 2000s (ILO and NITI Aayog studies), despite rapid firm-level expansion.

- Platform Economy without Productivity Gains: Many Indian unicorns (food delivery, ride-hailing) rely on labour abundance rather than technological upgrading, reinforcing low-wage equilibrium.

Way Forward

- Technology-Led Industrialisation: Promote adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies—automation, robotics, AI and advanced manufacturing—through targeted incentives and R&D support.

- Human Capital and Skill Deepening: Align skilling missions with industrial needs, focusing on technical education, apprenticeships, and continuous reskilling.

- Labour Market Reforms with Security: Balance flexibility with social security to encourage formal employment and productivity-linked wage growth.

- Strengthen Industrial Ecosystems: Develop integrated manufacturing clusters with plug-and-play infrastructure, logistics connectivity, and supplier networks beyond existing coastal hubs.

- MSME Upgradation and Scale: Support MSMEs in technology adoption, access to credit, and integration into global value chains.

- Stable and Predictable Policy Regime: Ensure consistency in industrial, trade, and tax policies to reduce uncertainty and encourage long-term investment.

- Export Competitiveness with Value Addition: Shift focus from low-cost exports to high-value manufacturing through standards, quality upgrading, and innovation.

- Balanced Wage Policy: Encourage wage growth aligned with productivity to induce innovation rather than suppress wages through labour abundance.

- Public–Private Collaboration: Leverage partnerships between government, industry and academia to drive innovation, technology diffusion, and skill development.

Conclusion

India’s manufacturing lag stems not only from policy choices like high public sector wages but from a deeper failure to induce technological upgrading. Without productivity-led manufacturing growth, India risks persistent jobless growth, rising inequality, and incomplete structural transformation.

Mains Question

- India’s manufacturing sector has failed to replicate the industrial success of East Asian economies. Examine the structural and policy factors behind this lag, and suggest measures to revitalise manufacturing-led growth.(250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Hindu

(UPSC GS Paper III – Security Challenges and their Management in Border Areas; GS Paper II – Governance, Centre–State Relations)

Context (Introduction)

Amid rapid maritime expansion and rising non-traditional security threats, India has established the Bureau of Port Security under the Merchant Shipping Act, 2025 to create a unified, statutory framework for port and coastal security governance.

What is the Bureau of Port Security (BoPS)?

- Statutory Basis: BoPS has been constituted under Section 13 of the Merchant Shipping Act, 2025 as a dedicated regulatory authority for port and ship security.

- Administrative Control: It functions under the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways, and is modelled on the Bureau of Civil Aviation Security.

- Core Mandate: BoPS provides regulatory oversight, coordination, and standard-setting for security of ships, ports, and port facilities across major and non-major ports.

- International Compliance: It is empowered to enforce global norms such as the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code, ensuring India’s ports meet international maritime security standards.

Why Was BoPS Needed? (Challenges in Coastal Security)

- Fragmented Security Architecture: Currently, coastal and port security responsibilities are divided among multiple agencies — Indian Coast Guard, Central Industrial Security Force, State maritime police, and the Navy — leading to coordination gaps and delayed response.

- Expanding Threat Spectrum: India faces growing risks of maritime terrorism, arms and drug smuggling, human trafficking, illegal migration, piracy, and poaching. Increasing digitalisation of ports has also exposed vulnerabilities to cyber-attacks on port IT systems.

- Rapid Maritime Growth: According to official data, India’s cargo handling rose from 974 MMT in 2014 to 1,594 MMT in 2025; inland waterways cargo increased eightfold to 145.5 MMT. Higher traffic amplifies security risks if governance does not keep pace.

- Absence of a Single Regulator: Earlier, no single statutory body existed exclusively for port security regulation, audits, and compliance monitoring.

How BoPS Addresses These Challenges

- Single-Point Regulatory Authority: BoPS acts as the nodal body for security oversight, reducing inter-agency overlaps and closing coordination gaps.

- Standardisation of Security Protocols: Under BoPS, the CISF is designated as a recognised security organisation to prepare uniform security plans, conduct risk assessments, and train personnel across ports.

- Graded Security Framework: Security measures will be implemented based on threat perception, ensuring flexibility without compromising vigilance.

- Cybersecurity Focus: BoPS is expected to host a dedicated cybersecurity division to protect port IT and logistics systems, in coordination with national cyber agencies.

- Information Sharing and Intelligence Coordination: BoPS will facilitate collection and exchange of maritime security intelligence, strengthening preventive and deterrent capacity.

Link with India’s Maritime Vision and Legal Reforms

- Maritime India Vision 2030: BoPS aligns with India’s goal of developing “best-in-class port infrastructure”, where security is integral to efficiency and investor confidence.

- Modernised Port Laws: The creation of BoPS complements the replacement of the Indian Ports Act, 1908 with the Indian Ports Act, 2025, along with the Coastal Shipping Act, 2025, aimed at ease of doing business, safety, and sustainability.

- Global Standing: Nine Indian ports now feature in the World Bank’s Container Port Performance Index, making robust security governance essential for maintaining credibility.

Concerns and Criticisms

- Maritime Federalism: Coastal States have raised concerns that new port laws expand Union control over non-major ports, potentially diluting State autonomy.

- Powers of Inspection: Critics argue that broad inspection and entry powers under the new laws lack explicit judicial safeguards, raising civil liberty concerns.

- Implementation Capacity: The effectiveness of BoPS will depend on staffing, technical expertise, and seamless coordination with existing maritime forces.

Way Forward

- Clear Centre–State Coordination Protocols to address federal concerns while ensuring uniform security standards.

- Capacity Building through specialised training in maritime and cyber security.

- Strong Accountability and Audit Mechanisms to balance security powers with procedural safeguards.

- Technology Integration using AI, surveillance systems, and real-time data sharing for proactive threat detection.

Conclusion

The Bureau of Port Security represents a critical institutional reform to match India’s expanding maritime footprint with a coherent security architecture. Its success will hinge on cooperative federalism, technological capacity, and transparent governance.

Mains Question

- India’s expanding maritime economy has exposed gaps in coastal and port security governance. Examine the role of the Bureau of Port Security in addressing these challenges and discuss the concerns associated with recent port law reforms.(250 words, 15 marks)

Source: The Hindu