Archives

(PRELIMS Focus)

Category: International Organisations

Context:

- Ukraine wants “real peace, not appeasement” with Russia, its foreign minister recently at the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

About Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE):

- Nature: It is a dynamic organization that is dedicated to promoting peace, stability, and security throughout Europe and Central Asia.

- Objective: It works for stability, peace and democracy through political dialogue about shared values and through practical work that makes a lasting difference.

- Origin: Its origin dates back to the early 1970s, to the Helsinki Final Act (1975) and the creation of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), which during the Cold War served as an important multilateral forum for dialogue and negotiations between East and West.

- Renaming: In 1994, the CSCE was renamed the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) to reflect these changes more accurately.

- Headquarters: Its headquarters is located in Vienna.

- Uniqueness: It is the world’s largest regional security organization.

- Member Countries: It consists of 57 participating States in North America, Europe and Asia. (India is not a member country).

- Governance: There are four decision-making bodies with delineated, distinct mandates namely;

- Summits: It is the highest decision-making body of the OSCE

- Ministerial Councils: The OSCE’s central decision-making and governing body

- Permanent Council: It is responsible for the day-to-day business of the Organization

- Forum for Security Co-operation: It deals with the politico-military dimension of security

- Leadership: The OSCE’s leadership includes the Chairperson-in-Office, the Secretary General, and the heads of its institutions and field operations.

Source:

Category: Science and Technology

Context:

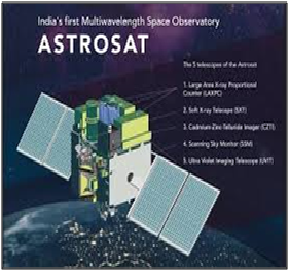

- The Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA) celebrated 10 years of India’s first space-based Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (UVIT), which is the main payload on AstroSat.

About AstroSat:

-

- Nature: It is the first dedicated Indian astronomy mission aimed at studying celestial sources in X-ray, optical and UV spectral bands simultaneously.

- Objective: It enables the simultaneous multi-wavelength observations of various astronomical objects with a single satellite.

- Collaboration: It is a collaborative project of ISRO and premier Indian research institutes with international partners (Canada, UK).

- Payloads: These include Ultra Violet Imaging Telescope (UVIT), Large Area X-ray Proportional Counter (LAXPC), Cadmium–Zinc–Telluride Imager (CZTI), Soft X-ray Telescope (SXT) and Scanning Sky Monitor (SSM).

- Coverage: The payloads cover the energy bands of Ultraviolet (Near and Far), limited optical and X-ray regime (0.3 keV to 100keV).

- Management: The spacecraft control centre at Mission Operations Complex (MOX) of ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC), Bengaluru manages the satellite during its entire mission life.

- Major functions of AstroSat:

-

- To understand high energy processes in binary star systems containing neutron stars and black holes.

- To estimate magnetic fields of neutron stars.

- To study star birth regions and high energy processes in star systems lying beyond our galaxy.

- To detect new briefly bright X-ray sources in the sky.

- To perform a limited deep field survey of the Universe in the Ultraviolet region.

Source:

Category: Defence and Security

Context:

- The Fifth edition of Joint Military exercise “Exercise Harimau Shakti -2025” commenced today in Mahajan Field Firing Range, Rajasthan.

About Exercise Harimau Shakti:

-

- Countries involved: It is a joint military exercise conducted between India and Malaysia.

- Objective: The aim of the exercise is to jointly rehearse conduct of Sub Conventional Operations under Chapter VII of United Nations Mandate.

- Origin: Started in 2012, it reinforces India’s Act East Policy and commitment to global peacekeeping frameworks.

- Significance: The exercise will foster strong bilateral relations between the two nations.

- Indian representation: The Indian contingent is being represented mainly by troops from the DOGRA Regiment.

- Other Military Exercises between India and Malaysia: These are Samudra Laksamana (bilateral maritime exercise), and Udara Shakti (bilateral air force exercise).

- Key Highlights of Exercise Harimau Shakti 2025:

-

- In this exercise both sides will rehearse drills to secure helipads and undertake casualty evacuation during counter-terrorist operations.

- Both sides will practice tactical actions such as cordon, search and destroy missions, heliborne operations, etc.

- Both sides will exchange views and practices of joint drills on a wide spectrum of combat skills that will facilitate the participants to mutually learn from each other.

- Sharing of best practices will further enhance the level of defence cooperation between Indian Army and Royal Malaysian Army.

Source:

Category: Economy

Context:

- Recently, NHAI received SEBI’s in-principle approval of registration to Raajmarg Infra Investment Trust as an Infrastructure Investment Trust (InvIT).

About Infrastructure Investment Trust (InvIT):

- Nature: It is Collective Investment Scheme similar to a mutual fund, which enables direct investment of money from individual and institutional investors in infrastructure projects

- Objective: It aims to provide retail investors with access to investment opportunities in infrastructure projects, which were previously only available to large institutional investors.

- Regulation: InvITs are regulated by the SEBI (Infrastructure Investment Trusts) Regulations, 2014.

- Similar to mutual funds: InvITs are instruments that work like mutual funds. They are designed to pool small sums of money from a number of investors to invest in assets that give cash flow over a period of time. Part of this cash flow would be distributed as dividends back to investors.

- Minimum investment: The minimum investment amount in an InvIT Initial Public Offering (IPO) is Rs 10 lakh, therefore, InvITs are suitable for high net-worth individuals, institutional and non-institutional investors.

- Tradable on stock exchanges: InvITs raise capital through IPOs and are then tradable on stock exchanges. Examples of listed InvITs include the IRB InvIT Fund and India Grid Trust.

- Parties involved: An InvIT has 4 parties namely; Trustee, Sponsor(s) and Investment Manager and Project Manager.

- INVITs are created by sponsors, who are typically infrastructure companies or private equity firms.

- The sponsor sets up the INVITs and transfers ownership of the underlying infrastructure assets to the trust.

- The trust then issues units to investors, which represent an ownership stake in the trust and thus the underlying assets.

- While the trustee (certified by Sebi) has the responsibility of inspecting the performance of an InvIT, sponsor(s) are promoters of the company that set up the InvIT.

Source:

Category: Environment and Ecology

Context:

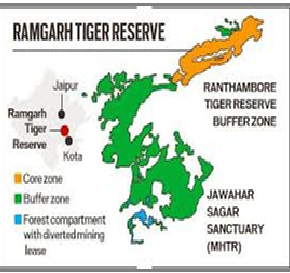

- Marking the state’s first inter-state tiger translocation and country’s second, a tigress is set to be airlifted from Pench Tiger Reserve to Ramgarh Vishdhari Tiger Reserve.

About Ramgarh Vishdhari Tiger Reserve:

- Location: It is located in Rajasthan’s Bundi district.

- Establishment: The Government of Rajasthan declared it a sanctuary under Section 5 of the Rajasthan Wildlife and Bird Protection Act, 1951 on 20th May, 1982. It was notified as a tiger reserve on May 16, 2022.

- Area: Spread over 1,501.89 sq.km., the reserve has a 481.90 sq.km. core area and a 1,019.98 sq.km. buffer zone.

- Importance: It is strategically positioned to serve as a crucial corridor between the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve to the northeast and the Mukundara Hills Tiger Reserve to the south.

- Associated rivers: The Mez River, a tributary of the Chambal River, meanders through the reserve.

- Topography: The reserve’s topography is characterized by the rugged terrains of the Aravalli and Vindhyan mountain ranges, interspersed with valleys and plateaus.

- Vegetation: It mainly consists of dry deciduous forests.

- Flora: The habitat is dominated by Dhok (Anogeissus pendula) trees. Other important flora includes Khair, Ronj, Amaltas, Gurjan, Saler, etc.

- Fauna: The area is dominated by leopards and sloth bears. Other important fauna include the Jungle cat, Golden jackal, Hyaena, Crested Porcupine, Indian Hedgehog, Rhesus macaque, hanuman langur, etc.

Source:

(MAINS Focus)

(UPSC GS-II – “Governance, Transparency & Accountability”; GS-III – “Technology & Its Applications”)

Context (Introduction)

Digital monitoring tools such as biometric attendance, facial recognition, geo-tagging apps, and photo-based verification are increasingly used in welfare delivery to curb corruption and enforce accountability. Evidence from MGNREGA, PDS, Poshan Tracker and frontline health services, however, shows mixed outcomes and new risks.

Why Governments Are Turning to Tech-Surveillance Tools?

- Accountability-Deficit: Chronic absenteeism, delayed service delivery, and petty corruption push governments toward tech-based enforcement mechanisms.

- Ease-of-Monitoring Narrative: Apps offer the appearance of real-time oversight, creating political incentives to adopt them regardless of their real effectiveness.

- Centralised Control: Digital systems allow higher bureaucratic layers to monitor frontline workers without investing in stronger local governance systems.

- Pressure for Quick Fixes: Complex administrative failures are seen as solvable through simple technological tools, avoiding deeper systemic reforms.

- Perception of Objectivity: Authorities often believe biometrics or photographs ensure foolproof verification, despite evidence of manipulation.

Limitations & Risks of Tech-Fixes in Welfare Delivery

- Manipulation Persists: Digital attendance is routinely gamed (e.g., NMMS photos fudged, ABBA misuse), proving that technology cannot eliminate human collusion.

- Exclusion Risks: Elderly, disabled, and remote beneficiaries struggle with biometric failures, weak connectivity, or app glitches, leading to welfare denial.

- Worker Demotivation: Excessive surveillance erodes dignity of frontline workers, shifting focus from service quality to compliance with app requirements.

- Privacy Violations: Photo uploads of breastfeeding mothers or home visits raise ethical concerns and weaken trust in welfare systems.

- False Sense of Accountability: Monitoring tools check presence, not performance—workers may appear compliant digitally without delivering quality services.

- Administrative Overload: Requirements like “100% verification of photographs” divert attention from program management to digital paperwork.

- New Corruption Channels: Officials can falsely claim “biometric failure” or demand bribes to resolve digital discrepancies.

- Agnotology Concern: The deliberate ignorance of failures suggests vested interests and commercial incentives influencing policy choices.

But Technology Also Offers Meaningful Opportunities

- Improved Transparency: Digital trails, as seen in Andhra Pradesh’s e-PDS system, reduce leakages when paired with community audits, unlike systems relying solely on biometrics.

- Real-Time Data: Apps can strengthen planning — Tamil Nadu’s Integrated Child Nutrition dashboard and Rajasthan’s e-Hospitalsystems show how analytics (not surveillance) can map stock-outs and service gaps.

- Reduced Middlemen: Direct digital records, similar to Kenya’s mobile-money welfare transfers, minimise manual manipulation when interfaces remain simple and staff-friendly.

- Targeted Interventions: Geo-tagging, used effectively in Brazil’s Bolsa Família monitoring, helps locate underserved habitations, enabling more rational deployment of health, nutrition, and sanitation services.

- Complementary Role, Not a Substitute: Technology supports — but cannot replace — local institutional reforms, as demonstrated by Indonesia’s village governance model, where apps assist audits but accountability rests with empowered councils.

Way Forward

- Strengthening Institutions: Empowering local bodies and social audits — as Philippines’ community-driven development model shows — ensures human oversight over digital processes.

- Investing in Workers: Training and supportive supervision, like Thailand’s upskilling of community health volunteers, build responsibility better than punitive surveillance apps.

- Reducing Last-Mile Burdens: Countries such as Estonia cut inefficiency by simplifying workflows before digitising; India must similarly reduce redundant photo uploads and paperwork.

- Context-Specific Design: Uganda’s mHealth projects succeed because apps work offline; India must adapt tools to low-connectivity regions to prevent exclusion of genuine beneficiaries.

- Ethical & Privacy Framework: The EU’s GDPR and Kenya’s Data Protection Act demonstrate how strict limits on biometric and photo-based data protect dignity and prevent misuse in welfare delivery.

- Participatory Technologies: Japan’s model of co-designing municipal apps with users shows that when frontline workers and communities shape the tool, accountability deepens, and compliance becomes organic.

Conclusion

Tech-surveillance tools in welfare may create the illusion of accountability, but without institutional reforms, they often substitute one form of manipulation for another. True accountability requires a shift from coercive monitoring towards cultivating responsibility, professional ethos, and trust within public systems. Technology can enable this journey—but cannot drive it alone.

UPSC Mains Question

- “Digital governance tools promise accountability but often deliver exclusion and surveillance.” Critically analyse the role of tech-based monitoring apps in welfare delivery in India. (250 words)

(UPSC GS Paper II – “International Relations: Bilateral, Regional and Global Groupings; India’s Foreign Policy”)

Context (Introduction)

President Putin’s 2025 visit to India amid escalating Russia–West tensions highlights New Delhi’s commitment to multi-alignment. India seeks deeper economic engagement with Moscow while carefully avoiding strategic decisions that could antagonise the U.S. and Europe.

Main Arguments

- Historical Depth : India values long-standing India–Russia defence and strategic ties, reflected in 25 years of annual summits and continued political signalling even when Russia faces Western sanctions and ICC warrants.

- Economic Re-engagement : New initiatives like a labour mobility agreement and an MoU to build a urea plant demonstrate efforts to sustain economic ties despite declining oil imports due to U.S. tariff surcharges and sanctions on Russian entities.

- Connectivity Vision : The Maritime Corridor plan and national currency payment systems aim to bypass sanctions bottlenecks and diversify trade routes, aligning with India’s larger de-dollarisation ambitions.

- Political Signalling : Mr. Modi receiving Mr. Putin in person conveys that India will not isolate Moscow at Western behest, reinforcing India’s foreign policy principle of strategic autonomy, not bloc alignment.

- Peace Narrative : India maintains consistent messaging on negotiated settlements in Ukraine, positioning itself as a potential interlocutor while avoiding openly criticising Russia — a calibrated diplomatic posture.

Challenges / Criticisms

- Western Sensitivities Defence, nuclear, and space deals were consciously avoided, showing India’s caution in not jeopardising ongoing FTA talks with the U.S. and EU or critical technology partnerships.

- Trade Constraints : India’s decision not to increase oil imports undermines the $100 billion trade target, reflecting the difficulty of balancing economic ambition with geopolitical risk.

- Sanctions Architecture : Stringent U.S.–EU sanctions on Russian banks and energy firms complicate payment mechanisms and risk secondary sanctions for Indian companies.

- Russia–China Axis : Russia’s deepening dependence on China narrows India’s space and raises concerns that Moscow may tilt towards Beijing on issues like the Indo-Pacific.

- Perception of Pendulum Diplomacy : Frequent swings between courting Russia and courting the West may undermine India’s credibility unless anchored in consistent, principled behaviour.

Way Forward

- Institutionalised Multi-Alignment: Adopt a France-style autonomy doctrine, embedding strategic independence in policy so that ties with Russia and the West evolve without appearing reactionary or episodic.

- Diversified Defence Sourcing: Gradually emulate Japan’s model of broad-based defence partnerships to reduce vulnerability to Russian supply-chain shocks while safeguarding legacy Russian platforms.

- Stable Energy Architecture: Build a long-term energy strategy like South Korea’s multi-supplier diversification, ensuring Russian energy remains an option but not a dependency.

- Economic Compartmentalisation: Create separate regulatory pathways for Russia-linked trade (similar to Turkey’s dual-track system), insulating such flows from Western regulatory pressure.

- Consistent Peace Diplomacy: Position India as an independent crisis mediator, akin to Brazil’s non-aligned diplomacy, signalling that autonomy means principled neutrality — not silence or partisanship.

Conclusion

Sustaining strategic autonomy requires India to avoid oscillations and instead cultivate structured engagement with both Russia and the West. A predictable, principle-driven foreign policy — not reactive balancing — will best protect India’s long-term geopolitical and economic interests.

UPSC Mains

- Amid intensifying Russia–West confrontation, Critically assess how India can maintain strategic autonomy. What opportunities and constraints shape India’s multi-aligned foreign policy? (250 words)