Archives

IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs – 21st October, 2016

INDIAN HERITAGE AND CULTURE

TOPIC:

General Studies 1

- Indian culture will cover the salient aspects of Art Forms, Literature and Architecture from ancient to modern times.

- Salient features of Indian Society, Diversity of India.

General Studies 2

- Important International institutions, agencies and fora- their structure, mandate.

“Why monuments would be worse off without the World Heritage status”

UNESCO defines a WHS as a place or environment of “great significance” or meaning to mankind. It may be a living urban city or a rural settlement, a natural landscape (an underground cave, for instance), a forest or a water body, an archaeological site (where excavations have revealed relics of the past) or a geological phenomenon.

Thus, it could be a natural site, a cultural site (which would be a traditional man-made settlement representative of a culture or cultures resulting from human interaction with the environment), or a site that’s a mix of both.

The largest number of World Heritage sites are in Italy (49) and China (45).

Note: Nations can submit no more than one nomination per year and competition is keen. To evaluate each year’s crop of nominations, UNESCO relies upon expert evaluations by the International Commission on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS).

Concerns over the impact of tourism on World Heritage sites

The increased tourist flow also has a flip-side. The Taj Mahal, the country’s most popular monument which became a World Heritage site in 1983, attracts one in every four foreign tourists visiting India.

Taj Mahal is recently ranked as the fifth most popular landmark based on travellers’ reviews and ratings. The list was topped by Machu Picchu in Peru.

Abrasions and the deposit of body oils are causing damage to the structure. Pollution has also been a worry for conservationists.

The effect of bringing people to a location unequipped to deal with the consequences of tourism seriously undermines the World Heritage program’s altruistic beginnings and goals.

However, the government is yet to take a call on limiting tourist flows based on a report submitted by the National Envrionmental Engineering Research Institute which looks at the impact of different levels of tourist footfalls.

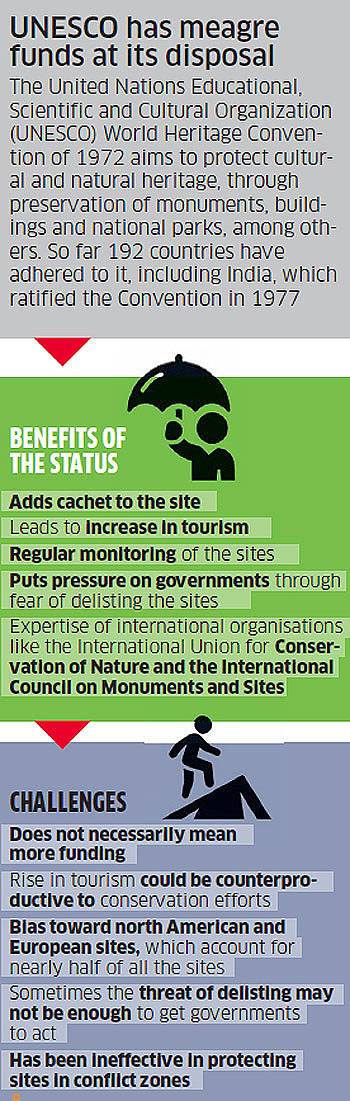

Concerns with funding

World Heritage tag does not necessarily mean more money for these sites.

Between 1983 and 2008, India received less than a million dollars from the World Heritage Centre (WHC) in financial assistance. Since 2008, India has not sought any funds.

For 2016-2017, the World Heritage Fund has $5.9 million at its disposal. However, it falls far short of covering the whole cost of implementing the Convention.

In other words, money is far too little to protect the world’s heritage and priority is given to the endangered sites.

In addition to the World Heritage Fund, assistance may be called forth from ―international and national governmental and non-governmental organizations and private bodies and individuals.

For instance, the Ajanta and Ellora Caves, which are also World Heritage sites, have received international financial assistance. The Japanese Bank of International Co-operation (JBIC) extended loans worth Rs 350 crore to the Indian government for conservation works and creating infrastructure for tourists at the caves between 1993 and 2013. But such instances of financial support are rare for Indian World Heritage sites.

Commentators have criticized that there are instances of bureaucratic wrangling, underhanded deals for money and influence between the Funding Committee and the Member States. They have begun to question whether UNESCO‘s position in international preservation has diminished significantly from the ―gold standard.

Also global funds may not be worth the effort required to get them, given the laborious, multi-step clearance from the government.

Therefore, effective funding and radical changes is needed if the UNESCO’s WHC is to remain an effective conservation tool.

However, it is quite evident that sites with World Heritage Tag get preference from the government over their peers without the honour.

For instance, the ASI spent Rs 1.4 crore on Elephanta in 2015-16, nearly twice as much as it spent on the Kanheri Caves in Mumbai, a collection of over a hundred caves dating back to the 3rd century BC. The Kanheri Caves are not on the World Heritage list.

Why monuments would be worse off without the World Heritage status?

World Heritage sites are in the ASI’s top category of monuments and they are first priority. Sites with World Heritage Tag get preference for funding from the government over their peers without the honour.

The biggest upshot of the World Heritage status is the rise in tourists at the site, especially those from other countries.

For instance, in 2015-16, Elephanta had 7.2 lakh Indian visitors, more than double the arrivals at Kanheri. In the same period, Elephanta got 36,570 foreign tourists, more than seven times the figure at Kanheri. "When foreign travellers plan their itinerary, this (World Heritage status) makes a huge difference.

Countries will have to identify sites they want considered for the World Heritage status, and this has led to criticism that some properties of real cultural or natural significance may be ignored. A country will have to first put its prospective sites on the tentative list and then decide which of those it wants to nominate for inclusion on the World Heritage list. India presently has 44 properties on the tentative list, with some having been on it since 1998. The list also has cities like Ahmedabad, Jaipur and Delhi.

Once a site is inscribed on the World Heritage list, it has to follow the monitoring guildelines of the WHC. All countries will have to mandatorily submit a report to the WHC on their sites every six years, and the WHC assesses them.

If a site faces threats to its conservation and the threats are not addressed, the WHC could put it on the list of sites in danger. Only after the country has done enough will the site be taken off the list. But if the country does not act, the site could then be delisted.

The process to remove a site from the danger list is a collaborative effort between the country concerned, the advisory bodies, the World Heritage Centre at UNESCO, and sometimes other countries who may provide funding or technical support.

Concerns over protecting the WHS

The WHC has come in for criticism for failing to protect sites like the Bamiyan Valley in Afganistan, where Buddha statues were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001, and the remains of the historical cities of Palmyra in Syria and Hatra in Iraq, both of which were damaged by the Islamic State terrorists.

The Manas National Park in Assam, which was inscribed in 1985, bore the brunt of the Bodo insurgency, which caused a sharp fall in wildlife populations. The site was put on the ‘danger’ list in 1992. The site was taken off the in 2011, eight years after the Bodo Accord was signed. Rhinos were reintroduced in Manas from the Kaziranga National Park, another World Heritage site, and the Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary. Manas is presently home to 28 rhinos and 25 tigers, among other animals.

An academic who has spent time researching at Manas and Kaziranga, says the World Heritage status is nothing more than a brand tag. "The government is not bound to give any more money because of it and the governing mechanism is according to the Wildlife Protection Act."

The WHC opened its first natural heritage management and training centre at the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, last year.

Concerns over Anthropogenic activities

India's three major natural World Heritage Sites - the Western Ghats, Sundarbans National Park and Manas Wildlife Sanctuary - are facing threats from harmful industrial activities like mining.

Activities such as mining, illegal logging, oil and gas exploration threaten 114 out of 229 natural World Heritage sites, including Sundarbans known for iconic Royal Bengal tiger, Western Ghats, one of the top biodiversity hotspots in the world, and the Manas Sanctuary in Assam, home to many endangered species including Indian rhinoceros.

While ecology of Western Ghats covering six states - Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala - is threatened by mining and oil and gas exploration, Manas Wild Life Sanctuary faces threat from dams and unsustainable water use.

Sundarbans in West Bengal and neighbouring Bangladesh have been hit by various activities including unsustainable water use, dams, wood harvesting, over-fishing and shipping lanes.

These sites are recognised as the world's most important protected areas like India's Great Himalayan National Park and Kaziranga National Park.

The Western Ghats supports the single largest population of endangered Asian elephants and vulnerable Indian bison.

These iconic places face a range of threats, including climate change. Removing pressure from harmful industrial activity is therefore critical to increase the sites' resilience.

According to International Union for Conservation of Nature, which helps the world find pragmatic solutions to most pressing environmental and developmental challenges, natural World Heritage sites are not just important environmentally, they also provide social and economic benefits.

Two-thirds of natural sites on the UNESCO World Heritage List are crucial sources of water and about half help prevent natural disasters such as floods or landslides, according to an IUCN report.

Picture Credit: http://img.etimg.com/photo/54757625/1.jpg

The way ahead:

Sustainable tourism programme, involving stakeholders or interested parties, including government agencies, conservation and other non-governmental organisations, developers and local communities in planning and management is of paramount importance.

UNESCO must have mechanisms with which to effect real change when governments do not comply with the basic premises of preservation.

Member states should no longer be allowed to submit their own nominations for inclusion directly to the Committee. Several independent groups, comprised of anthropologists, archaeologists, ecologists, and others, should research and recommend worthy sites to the World Heritage Committee. This extra layer of vetting will help to quell extensive lobbying and bartering by potential host countries on behalf of their sites.

The World Heritage program must bring in money from various sources in order to fund its programs. As it stands, corporations and philanthropists are hesitant to sink money into UNESCO because of its extensive bureaucracy and lack of transparency. If the World Heritage Committee can reassure potential donors regarding the exact use of their funds, it will go a long way toward gathering the capital necessary to carry out the program‘s mission. At the same time, an influx of new potential donors will ensure that the program is not pressured to compromise on its goals by organizations that use money as leverage for political and economic influence.

The creation of the World Heritage Convention was a significant step toward recognizing and preserving the greatest cultural and natural aspects of the world. However, its implementation has derailed, and the World Heritage program needs to realign its procedures with its goals.

Connecting the dots:

- Does UNESCO inscription play a significant role in tourism destinations performance? Also discuss the UNESCO's role in relation to protecting the world heritage site.

- Discuss the benefits of a site getting awarded as World Heritage Site by UNESCO? Also discuss some of the concerns faced by World Heritage Sites in India with suitable examples.

Related article:

World Heritage and India’s World Heritage List

NATIONAL/ECONOMY

TOPIC:

General Studies 2

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

- Functions and responsibilities of the Union and the States, issues and challenges pertaining to the federal structure, devolution of powers and finances up to local levels and challenges therein.

General Studies 3

- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment.

- Inclusive growth and issues arising from it.

GST Council meet- Issues and way ahead

In news: A two day meeting of Goods and Services Tax (GST) Council concluded recently with no consensus on GST rate and other issues. We will now briefly look into the issues and further course of action sought to be taken.

What is GST Council?

- According the GST Bill, the President must constitute a GST Council within sixty days of the Act coming into force.

- The GST council is headed by Union Finance Minister and comprises finance ministers or other representatives of states.

- The Council will make recommendations to the Union and the States on important issues related to GST, like the goods and services that may be subjected or exempted from GST, model GST Laws, special provisions for certain States, etc.

- The decisions of the GST Council will be made by three-fourth majority of the votes cast. The centre shall have one-third of the votes cast, and the states together shall have two-third of the votes cast. Thus, neither the states together nor the Centre alone can change the GST.

Tasks done till now

- The GST Council's first meeting in September had finalised area-based exemptions and how 11 states, mostly in the North-East and hilly regions, will be treated under the new tax regime.

- Till now, 6 issues have been settled by the GST Council, including finalisation of rules for registration, rules for payments, returns, refunds and invoices.

- The Centre and states had also reached an agreement on keeping traders with annual revenue of up to Rs. 20 lakh out of the GST barring 11 northeastern and hill states, where the threshold will be Rs. 10 lakh.

- The issue of dual control over small traders was resolved but it resurfaced in latest meeting and now it is yet to be resolved.

New proposals

Slab structure

- The finance ministry has proposed a four-slab structure (6-12-18-26 percent) and there is near unanimity on it.

- In 2015, a committee headed by Chief Economic Adviser had recommended a revenue neutral rate (RNR) of 15-15.5% and standard rate of 16.9-18.9% for the proposed GST and a high rate of 40% for luxury goods.

- The four-slab structure is seen as the government’s way of dealing with opposition demand that the rate should not go beyond 18% as well as protecting revenues of states.

- The higher rate for services under the indirect tax regime is proposed to be 18%, while essential services such as transportation are proposed to be taxed at 6% or 12%.

- However, no consensus as yet has been arrived at it.

State compensation

- The GST Council finalised the compensation formula for states for potential revenue loss, converging at an assumption of 14% revenue growth rate over the base year of 2015-16 for calculating compensation for states in the first five years of implementation of GST.

- States getting lower revenue than this would be compensated by the Centre.

Inflation

- The total impact of the proposed rate structure on Consumer Price Index (CPI)-based inflation rate will be (-) 0.06%.

- The inflation impact on constituents of CPI such as health services, fuel and lighting and clothing is estimated to be 0.56%, 0.05 % and 0.23%, respectively, while for transport it is estimated at (-) 0.65%, education at (-) 0.08 % and housing at (-) 0.09%.

- GST rate should not be regressive in nature and be such that the existing revenues of states and Centre are protected and the impact on CPI inflation is minimal.

Cess on GST

- The centre has proposed a cess on the highest slab of 26%, which many states have opposed and tax experts have criticised.

- This cess will be on luxury goods (high-end cars) and ‘sin’ goods like tobacco, cigarettes, pan masala and aerated drinks.

- Though some term it as a clever move. The states that stand to lose revenue will need to be compensated and the states that gain are not going to give money for this. Hence, the Centre will then have to resort to this cess which will cushion the impact on the Consolidated Fund.

- Earlier, there was a proposal to subsume all cess levies in the GST, several of them introduced by the present NDA government. However, now the finance ministry is keen on additional cess than 40% slab suggested by CEA for luxury and demerit goods.

Administration control over assesses

- Earlier, the council had decided that states would have sole administrative control over assesses having an annual turnover of Rs 1.5 crore. Above that, both the states and the Centre would have control.

- The Centre would have sole control over assesses in the services sector right from the beginning till the time states have a mechanism to monitor service tax assesses.

- However, that consensus broke down later as a few states said they also monitor some service taxes even now, such as entertainment tax and as such should have control over that.

Expert views and opinion

On slab structure

- The GST is supposed to be the final step towards simplifying the indirect tax regime. This kind of a structure will take it back to the pre-VAT era (the regime which replaced sales tax in 2005) where there were multiple rates within and across states

- The only consolation will be that GST rates in the slabs will be uniform across states.

- Thus, with this structure, there will be hardly any way forward.

- A member of 14th Finance Commission has pointed out that this could also lead to the creation of an inverted duty structure. (An inverted duty structure is making manufactured goods uncompetitive against finished product imports in the domestic market as finished goods are taxed at lower rates than raw materials or intermediate products.)

- These multiple tax rates will increase compliance costs as well as administrative costs. More importantly, it will lead to intense lobbying by industry groups – everyone will want to be in the lower tax slab.

- The blanket 18% rate is not possible, rather a two-slab structure in the 20-22% range would have been better. Though one rate is viable but two slabs will be needed to politically sell the tax reform.

- Across the European Union the GST has only two rates with the exception of Denmark which has just one rate.

On cess

- The maximum rate of 26% for demerit or luxury goods may harbour more goods than initially envisaged, which will make them costlier. Also since cesses would be outside the GST, the present cascading may continue raising the tax burden.

- Other option instead of cess can be increasing the clean energy cess, which is not part of GST, and raising the rate on gold — which is now proposed to be taxed at 4%— to 6%.

- Also, the tobacco tax is only on cigarettes which constitutes only 11% of the market. The Centre should seriously consider bringing in other forms such as chewable tobacco, gutka and bidis into the net.

Conclusion

- There shouldn’t be sub optimal solutions and haste in implementation of GST.

- Care has to be taken that items being consumed by upper middle class and rich, which are being taxed at higher rate presently, should not be taxed at a rate lower than their present tax incidence, while items of mass consumption should not be taxed at a higher rate.

- It is a positive sign that Centre and states did manage to reach a broad agreement on the formula for compensation to loss-incurring states and a cess over the peak rate to fund the compensation. Now the hurdle of Administrative Control over tax assesses has to be overcome.

- Finance Minister has set November 22 target to resolve all operational issues with State representatives in the Council so that the rates and implementation modalities could be codified into law and passed by Parliament in the winter session. And the GST can be rolled out from April 1, 2017.

Connecting the dots:

- The GST council can be called a true federal body. Do you agree? Examine.

- The GST rate structure is not the sole important factor of GST bill. Many other concurrent issues play an equally important role in making India an economic union. Discuss.

MUST READ

Frames of reference- Triple talaq

A vote on referendums

Myths about Israel’s security model

At ease with the world

The Way Forward from Paris

Strengthening India’s energy security

Regime change at the Reserve Bank of India

Will Modi’s target of doubling Brics trade by 2020 materialize?

The unfinished business of job creation