IASbaba's Daily Current Affairs (Prelims + Mains Focus)- 24th February 2018

Archives

(PRELIMS+MAINS FOCUS)

Scrutiny of H-1B visa tightened

Part of: Mains GS Paper II- International relations

Key pointers:

- The U.S announced fresh measures to tighten the scrutiny of H-1B visa petitions, mandating fresh documentary requirements for workers at third-party worksites.

- The companies filing H-1B petitions for their employers will have to associate a particular project to the individual visa, which could be approved only for the duration of the project.

- The measures are intended to bring the client-vendor-employee relations in business models based on bringing high-skilled H-1B workers to America under closer scrutiny.

- The new move will mean H-1B visas may be issued only for the period for which an employee has work at a third-party worksite.

- The move will impact Indian IT companies that place H-1B employees at American companies that contract them, by imposing more paperwork and processing hurdles.

Article link: Click here

India's policy towards Rohingya

Part of: Mains GS Paper II- International relations

Key pointers:

- India is planning to expand the scope of assistance to pave the way for return of nearly seven lakh Rohingya (Arakanese Muslims) refugees from Bangladesh to Myanmar.

- The project is expected to help Bangladesh significantly, which is desperately seeking India’s support in ensuring safe return of the refugees.

Indian plan

- India was prompt in sending 7,000 tonne of relief assistance for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh beginning in last year.

- This was followed by a $25-million development programme to help Myanmar build the necessary infrastructure to rehabilitate Rohingyas in the troubled Rakhine State.

- India has taken a long-term view of the problem, avoiding quick-fix solutions.

- The project was spread over five years and refugee rehabilitation plan includes two layers of transit camps before ensuring safe rehabilitation in their villages in Rakhine.

Security threat:

- Security experts in Bangladesh and India are unanimous that Rohingya refugees are adding to the security threat to the region.

- The Chittagong area, bordering Myanmar, where refugees are camped has been a hotbed of Islamic fundamentalism and provided shelter to the secessionist forces in the North Eastern India, in the past.

- The militant activities (in the North East) have come down after the Sheikh Hasina government clamped down on Islamists. However, the situation turned for the worse after the arrival of the Rohingyas.

- Bangladesh is afraid that disturbance in Chittagong may impact its growth potential. Chittagong has the country’s only sea port and is a destination of major investments from India, Japan and China.

- Both China and India are heavily investing in port and allied infrastructure in Rakhine State and are keen to invest in deep sea port in Chittagong.

Given China’s influence in Bangladesh and Myanmar; the stakes are high for India. While China is keen to keep international forces out of the Rakhine dispute; India is trying to walk the tightrope of taking along both Bangladesh and Myanmar governments towards a viable solution for the Rohingya crisis.

Article link: Click here

India and Germany: Pact for smart city coopertion

Part of: Mains GS Paper III- Infrastructure

Key pointers:

- India has signed a MoU with Germany to develop modules for providing urban basic services and housing for smart cities.

- The MoU signed between Union Ministry for Housing and Urban Affairs and the German development agency GIZ would develop and apply concepts for sustainable urban development providing urban basic services and housing in select cities as well as smart cities in India.

- GIZ would contribute up to €8 million for the project which would run for a period of three years.

Article link: Click here

(MAINS FOCUS)

NATIONAL

TOPIC:

General Studies 1:

- Social empowerment

General Studies 2:

- Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation.

- Welfare schemes for vulnerable sections of the population by the Centre and States and the performance of these schemes

The "Unwanted girls" in India

Introduction:

India has 63 million “missing women.” The 2018 Economic Survey gives us a powerful new number: India has twenty-one million “unwanted girls”. This number describes the girls who are born but not treated well. Crafting a new statistic that brings a spotlight to this problem will be an important legacy of the Economic Survey.

Who are “Missing women”?

- These are the girls and women who would be alive today if parents were not aborting female foetuses.

- Girls getting less food and healthcare add to this count by raising female mortality.

Amartya Sen raised this problem in 1990 with an article titled “More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing”. He counted the missing women across several countries such as India, China and Pakistan. Many people knew the problem existed, but Sen’s number, called out in the title of his article, made the problem salient. Today, there are 63 million fewer women counted in the Census in India than there naturally should be.

Who are “Unwanted girls”? These are girls who are alive but likely disfavoured by their parents. They receive less healthcare and schooling, with life-long effects on their well-being. These girls are more precisely described as “less wanted” children. They are daughters that parents gave birth to when they were really hoping for a son. There are twenty-one million unwanted girls under the age of 25 in India.

Common pattern of childbearing:

A couple wants to have two children, ideally one son and one daughter, but it’s especially important to them to have at least one son. If they have two daughters in a row, they will keep having children until they get a son. In such cases, the last child in the family is a boy. By aggregating all families, it is seen that the sex ratio of the last child (SRLC) is male-skewed.

SRLC is thus a revealing measure of parents wanting sons.

- The fervent desire for sons in India is not a feature of all less economically developed societies. For example, in the historical US, there wasn’t a male-skewed SRLC.

- The Economic Survey's analysis revealed that even Kerala and Assam have a male-skewed SRLC; if we only tracked missing women, these states would look problem-free.

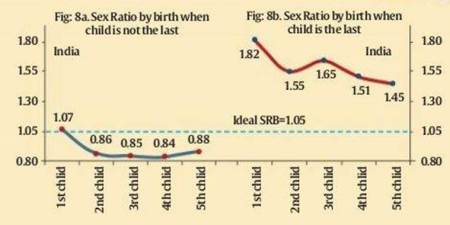

Pic credit: http://images.indianexpress.com/2018/02/epaper.jpg?w=450

In the figure above (from Economic Survey 2018), the right panel shows that last children are disproportionately male. The left panel shows that non-last children are more female; that’s because the child being female led the parents to keep having children in their quest for a son.

Issue:

Many couples have a girl when they were hoping for a boy. If the girls are nonetheless treated equally, this would not be much of a problem. Unfortunately, girls get fewer resources than boys. Even if parents treat their children equally, girls are disadvantaged by being in families with fewer resources to spend per child. Moreover, parents who passionately want sons, unsurprisingly, favour them once born. Boys are more likely to get immunisations.

- India shows a gender gap in stunting compared to other parts of the world, consistent with girls consuming less nutritious food.

- One study found that one year after parents were advised that their child needed surgery to correct a heart defect, 70 per cent of the boys but only 44 percent of the girls had undergone the surgery.

This is why having 21 million unwanted girls is unacceptable.

Way forward:

- Improve women’s earnings opportunities so that dowries are lower and women have more say in family decision-making.

- Better options for people to support themselves in old age, such as a good pension system, would make having a son less paramount to couples.

- We also need more efforts that take on society’s norms and try to reshape them so that people start valuing daughters as much as sons.

Conclusion:

A decline in the number of unwanted girls isn’t necessarily progress. Unwanted girls arise when parents keep having more children to obtain a son. Couples are becoming more reluctant to have large families and are gaining better access to ultrasound. “Trying again” might give way to more sex-selection. It will not be progress if we achieve fewer unwanted girls at the cost of more missing women. The goal should be for both numbers to come down.

Connecting the dots:

- While 'missing girls' is an issue well know, the latest economic survey raised the issue of "unwanted girls". Who constitutes unwanted girls? Discuss the reasons behind ans ways to solve the issue.

NATIONAL

TOPIC: General Studies 2:

- Parliament and State Legislatures – structure, functioning, conduct of business, powers & privileges and issues arising out of these.

The tussle between political executive and the bureaucracy in Delhi

Why in news?

The chief secretary (CS) of Delhi was reportedly roughed up by two MLAs in the Chief Minister's (CM’s) presence. One has heard of humiliation of officers before, but seldom involving the chief secretary.

The CS is not an ordinary bureaucrat. He is the head of the civil administration in the state or union territory, an officer who represents not just his own service but all services within the civil administration. His word in sorting out contending arguments and dissension among officers is final. It is his duty to run an efficient administration and give the CM fair and impartial advice. In Delhi, the CS has an even more challenging role — he has to report simultaneously to the CM and the lieutenant governor (LG) and walk a tightrope between the vision and concerns of both, even when they are not always on the same page.

Background:

The capital’s asymmetric division of powers between the elected and the selected has been an issue in recent times. It vests the LG with absolute powers without corresponding accountability and leaves the elected chief minister faced with complete responsibility but without requisite powers. The basic principle of parliamentary democracy is that the elected executive decides policies and programmes while the bureaucracy executes them. There can be occasional friction. But overall, the two arms of the executive work in tandem, as a single, cohesive branch. In the eyes of the law, the actions of secretaries are actions of ministers. On occasions when secretaries disagree with their ministers, the latter either agree with or overrule the babus. It is upon a CS that a CM is dependent for governance and delivery.

The Conflict:

The MHA, vide a notification dated May 21, 2015, added a fourth subject, “Services”, to the existing list of three subjects of Public Order, Police and Land which were already reserved with the Centre. Through a judgment on August 4, 2016, the Delhi High Court upheld the notification, ruling that “Services” was outside the domain of Delhi government. The high court also ruled that the “aid and advice” of the council of ministers is not binding on the LG. Hence, the elected executive in Delhi doesn’t have even a modicum of control or authority over government employees- from a peon to the chief secretary, the transfer, posting, appointment, creation of posts, service conditions, vigilance matters, leave sanction.

- Many appointments and transfers in the bureaucracy are made by the GOI without taking CM into confidence.

- The Delhi CS also coordinates with multiple authorities and agencies outside the Delhi Government. The performance of a CM is thus incumbent upon the performance of his CS and the secretaries of other departments with the CS at the top. But the Delhi CM can’t even pick a deputy secretary, leave aside his CS and secretaries. They are appointed by the LG without consulting either the chief minister or minister concerned.

- By vesting the LG with “Services” and the veto power on every aspect of governance, the Centre has made him the primary decision-making authority even with respect to transferred subjects. He convenes and chairs meetings on these subjects, where the chief minister and other ministers may or may not be invited.

- Cabinet decisions remain pending for long periods at the LG’s office. For example, the policy decision to establish 1,000 Mohalla Clinics was approved by the cabinet in November 2015 but the LG raised queries on multiple occasions and the project remained stalled for two years.

The Delhi government’s petition challenging the Centre’s notifications was heard by a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in December 2017. The order is since reserved.

Way ahead:

The AAP has for long complained that the Centre is paralysing its executive functions through the Lt. Governor and that the bureaucracy is refusing to obey government orders. But the proper response to this is to keep pushing for the constitutional changes that will give Delhi full statehood rather than targeting police officers and civil servants. Both the Centre and the Delhi government must work together to see that the administration is not brought to a halt in the Union Territory.

Conclusion:

The very concept of parliamentary democracy is at stake. The current imbroglio is only a manifestation of a deep-rooted malaise. It is time to address the structural malaise afflicting Delhi’s body politic.

The two pillars- the political executive and bureaucracy- need to hold the structure together, or else one would develop cracks and bring the other down with it or lead to a go-slow which would prevent doing things that matter the most.

Connecting the dots:

- The capital’s asymmetric division of powers between the elected and the selected has been an issue in recent times. Analyze.

MUST READ

The champions of clean air

Adopting a wait and watch approach

Grid staility is key

Canary in coal mine

When technology drives farming